The Monroe Brothers were one of the most popular

duet of the 1920s and 1930s. Charlie played the guitar, Bill played the

mandolin and they sang in harmony. When the

brothers split up, both went on to form their own bands.

Bill Monroe & The Blue Grass Boys soon

became a very popular act. Bill's new band was

different because of playing folk music with overdrive (Lomax).

Bill used the old music, but he invented bluegrass with it. In that day it was Punk, it was Hip-Hop. He took the old music and he made it new. (J. Ritchie)

He incorporated songs and rhythms from gospel, country and blues repertoires, and

settled on mandolin, banjo, fiddle, guitar and

bass as the format for his band.

As an ensemble musical form bluegrass reflects and echoes not only its rural roots but also the urban and industrial life from which it emerged. As on an assembly line, each musician has a special part to sing and a special job to do on his or her instrument. (Rosenberg)

In 1946, banjo player Earl Scruggs

and guitar player Lester Flatt

joined the band. Scruggs and Flatt eventually formed their own

group, The Foggy Mountain Boys, and included the dobro guitar into their

band format. By the 1950s, people began referring to this style

of music as bluegrass. Bluegrass bands

began forming all over the country. By the early 70s hundred of bluegrass festivals sprung up and that was where

Carl Fleischhauer and Neil V. Rosenberg entered the game.

Bluegrass Odyssey

is Fleischhauer's legacy of accompanying the bluegrass community

with his camera for nearly twenty years, interspersed with Rosenberg's narrative.

In the first chapter, "Intensity," we offer a group of photos chosen to convey first impressions of the music itself. The intensity of bluegrass performance was one of the things that attracted us to the music.

It's hard work, yet they seem to be relaxed and happy.

The lyrics often tell sad stories at toe-tapping or breakneck speed.

It's hard work, yet they seem to be relaxed and happy.

The lyrics often tell sad stories at toe-tapping or breakneck speed.

The pictures in the second chapter, "Destination," follow our own experience as our interest expanded from the music to its cultural context, from the sound to ethnography: musical instrument merchants, an Opry star grabbing a meal before the show, and a cross section of performance venues.

The third chapter, "Transactions," documents the production of sound recordings, paid performances, the sale of merchandise. But the chapter also highlights the nonmonetary exchanges that occur within these activities--for example, determining the sequence of songs in a set or the order of bands during a festival afternoon.

In the fourth chapter, "Community," the pictures interpret the human connections that tie individuals together. The fifth chapter, "Family," surveys one such connection, principally among performers.

The last chapter, "The Monroe Myth," is a meditation on an individual--arguably the leading figure in bluegrass music--and his family. Words and pictures take you on the road with Monroe, visiting his birthplace in Rosine, Kentucky,

and the graveyard in which his parents are buried.

203 photographs cover festivals and bars,

rednecks and hippies alike, during an era

when most of the founders were still alive and actively performing:

Bill Monroe himself,

Lester Flatt,

Earl Scruggs,

Ralph Stanley,

The New Grass Revival etc.

From western-style suits and shirts, scarves or neckties, and hats

to performers who imported repertoire, musical sensibilities, grab, hair length, and other trappings of countercultural style from rock.

Until the 1970s bluegrass musicians sang and played into one or two microphones. With four, five, or six musicians onstage using acoustic instruments without electric pickups, distance from and direction toward the microphone determined much of what the audience heard. The legendary choreography of Lester Flatt, Earl Scruggs, and the Foggy Mountain Boys enabled them to gang around the mike to deliver five-part harmony, along with his rhythm guitar and the backup work on the banjo and on the dobro. The dynamics of the music dictated dramatic shifts--movements toward and away from the microphone as instrumental breaks followed vocals. The first-generation bluegrass leaders spoke of their music in sports terms--the man at the mike was the batter or ball carrier. During the 1970s the number of microphones used onstage began to increase. In the mid-1990s, Doyle Lawson and Quicksilver spearheaded a return to the old single-mike technology, bringing back the choreography and blending that charmed early bluegrass audiences.

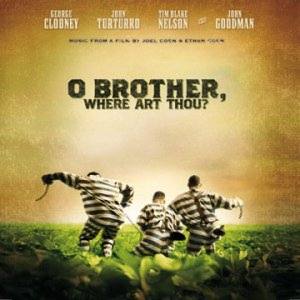

By the way, did you see

O Brother Where Art Thou?

The film is already two years old, but the soundtrack is still really hot

and the music goes from strength to strength.

What John Travolta's "Urban Cowboy"

achieved for country music in 1980,

has been revived twenty years later again by the Coen brothers.

O Brother topped the country charts last year and won five Grammy awards this year,

including an award for Album of the Year, defeating Bob Dylan and U2.

T-Bone Burnett was honoured as Producer of the Year.

The album also won best Compilation Disc, Country Collaboration with vocals

("I Am a Man of Constant Sorrow"), and best Male Country Vocal

(Ralph Stanley's "O Death").

Few people gave a bunch of little-known country musicians much chance of walking away with one of the most prestigious awards at the Grammys.

It has sold more than four million copies and has been one of the most unexpected hits of recent years.

Variously described as bluegrass, roots, mountain music and old-time country, it contains rustic sounds of harmonies, gospel choirs, mandolins, guitars, violins and banjos.

First popular in the 1920s and 1930s, the styles owe their comeback to the comedy film by Joel and Ethan Coen, which is based on Homer's Odyssey and stars George Clooney.

Veteran musician and producer T-Bone Burnett went about finding the songs for the film with singer-songwriter Gillian Welch.

One of the inspired choices was to revive a tune called I Am A Man Of Constant Sorrow, a folk song from the Appalachian mountains first recorded in 1922.

In the film, it became the anthem that made Clooney's band, The Soggy Bottom Boys, Depression-era stars.

In real life, it was recorded by Dan Tyminski, Harley Allen and Pat Enright.

Mr Tyminski provided the singing voice for Clooney on the film, and had to warn his wife, Elise, the first time they watched it that when Clooney would sing, she would really hear her husband's voice.

Your voice coming out of George Clooney's body? Dan, that's my fantasy! she replied.

While the film was an arthouse hit, nobody expected its music to go on to have so much success that it has taken on a life of its own.

First there was an O Brother concert in Nashville, then a documentary that had its own soundtrack, a United States tour and an O Sister album.

Mr Burnett also won a Grammy for a follow-up CD, Down from the Mountain.

And it has all happened with little radio airplay.

It may not be chart material - but that may be why so many people like it.

(BBC News)

Now, is there another Nashville? ...

... with a kind of music so distant from what the

city's commercial center cranks out as to be from a different planet. It

thrives in the community's nooks and crannies like a cluster of quietly

smiling mountain wildflowers in the shadow of those cultivated hothouse

blooms that flaunt their colors on radio stations from coast to coast.

The soundtrack celebrates this gentle music. What this seemingly ethnic sound is, is country

music. Or at least it was before the infidels of Music Row expropriated

that term to describe watered-down pop/rock with greeting-card lyrics.

This original country sound first flowered during the Depression. It was fertilized by blues,

gospel, string-band hoedowns, Appalachian balladry, work songs and

vaudeville hokum. Its practitioners were small-time entertainers who led

itinerant lives as they traveled from one schoolhouse show to the next,

from one radio barn dance to the next, from one makeshift recording

studio to another.

Despite the hard economic times, record companies and radio stations

discovered an enormous hunger for the homey sounds of The Carter Family,

the rowdy blues of Jimmie Rodgers, the saucy humor of Uncle Dave Macon,

the dazzling fiddling of Arthur Smith and the scintillating blues moans

of countless slide guitarists, harmonica men and jug-band songsters. That

hunger for emotional truth gave us our multi-million dollar music

industry.

The razzmatazz of western swing, the whipped-dog whine of honky-tonk

music, the creamy crooning of singing cowboys, the itchy-pants yelp of

rockabilly and the suburban gleam of The Nashville Sound seemed to drown

out the innocence of this rustic, acoustic kind of country. But it has

survived. Now called "old-time music" this style thrives at the more than

500 bluegrass festivals, fiddle contests and folk gatherings that are

staged every year in America.

You won't hear it on country radio. And it flies beneath the commercial

radar of most record shops. So for those whose musical tastes are shaped

by the great, gray behemoth that is the modern entertainment business,

this music does sound obscure. Even exotic.

The reason for our using so much of the era's music in the movie was

simple, explains Ethan Coen. We have always liked it. The mountain

music, the delta blues, gospel, the chain-gang chants, would later evolve

into bluegrass, commercial country music and rock 'n' roll. But it is

compelling music in its own right, harking back to a time when music was

a part of everyday life and not something performed by celebrities. That

folk aspect of the music both accounts for its vitality and makes it fold

naturally into our story without feeling forced or theatrical.

(Extra TV)

This original country sound first flowered during the Depression. It was fertilized by blues,

gospel, string-band hoedowns, Appalachian balladry, work songs and

vaudeville hokum. Its practitioners were small-time entertainers who led

itinerant lives as they traveled from one schoolhouse show to the next,

from one radio barn dance to the next, from one makeshift recording

studio to another.

Despite the hard economic times, record companies and radio stations

discovered an enormous hunger for the homey sounds of The Carter Family,

the rowdy blues of Jimmie Rodgers, the saucy humor of Uncle Dave Macon,

the dazzling fiddling of Arthur Smith and the scintillating blues moans

of countless slide guitarists, harmonica men and jug-band songsters. That

hunger for emotional truth gave us our multi-million dollar music

industry.

The razzmatazz of western swing, the whipped-dog whine of honky-tonk

music, the creamy crooning of singing cowboys, the itchy-pants yelp of

rockabilly and the suburban gleam of The Nashville Sound seemed to drown

out the innocence of this rustic, acoustic kind of country. But it has

survived. Now called "old-time music" this style thrives at the more than

500 bluegrass festivals, fiddle contests and folk gatherings that are

staged every year in America.

You won't hear it on country radio. And it flies beneath the commercial

radar of most record shops. So for those whose musical tastes are shaped

by the great, gray behemoth that is the modern entertainment business,

this music does sound obscure. Even exotic.

The reason for our using so much of the era's music in the movie was

simple, explains Ethan Coen. We have always liked it. The mountain

music, the delta blues, gospel, the chain-gang chants, would later evolve

into bluegrass, commercial country music and rock 'n' roll. But it is

compelling music in its own right, harking back to a time when music was

a part of everyday life and not something performed by celebrities. That

folk aspect of the music both accounts for its vitality and makes it fold

naturally into our story without feeling forced or theatrical.

(Extra TV)

The soundtrack kicks off with James Carter's "Po Lazarus",

recorded by the late Alan Lomax (see news section).

His daughter Anna Lomax-Chairetakis explains:

The opening song of the soundtrack and

the film is a field recording that

Alan made in the 1950s in Parchment

Penitentiary in Mississippi.

That's interesting too, because he

first had gone to Parchment with his

father in the early '40s with a disc

recorder. And when the tape machine

arrived he rushed down with paper

tape, which was all that was

available then, and recorded the

same people.

Then in the late '50s he went with

stereo, [making] the first field

recordings in stereo. And so that

song "Po' Lazarus" was one that he recorded in 1959.

It's played in its entirety --

that's the beauty of it.

They let it play out to the end.

It's not used as sort of a little

piece of effect, it's really given

its full beauty. Later on in the

movie there's a song called "Didn't

Leave Nobody But The Baby," which is

a lullaby that he recorded, sung by

a woman named Sydney Carter from

Senatopia, Mississippi. T-Bone Burnett made

a very nice arrangement of it, and

he added some verses. He had beautiful taste,

instead of distorting it or

cheapening it or something like

that. It was sung by Emmylou Harris

and Allison Krause. It's very pretty.

(Tech TV)

So in the end, we don't want to care too much about any mistakes during the making of the movie.

The beer bottle behind John Goodman in the picnic scene is

a modern day Budweiser bottle. --

In the scene where George Clooney and the guys meet Baby

Face, the money flying out from the back seat is currency from

today not the 20's or 30's. --

At the end of the movie when they sing "you are my

sunshine" they movie into a L.S. and you can see that the words

aren't synched in to their lips. --

While the three convicts and Tommy Johnson are recording

"A Man Of Constant Sorrow", you can see a clock behind George

Clooney. If you pay attention, you can see the hands of the clock

are in a different position every time the shot changes. --

The film takes place in the Thirties. The song "You are My

Sunshine" is featured, but was not recorded by Jimmie Davis (its

composer) until 1940 ...

(Movie Mistakes)

If you haven't seen the film yet, do it!

If you don't like movies, get the CD anyway!

T:-)M

Fleischhauer, Carl & Neil V. Rosenberg Bluegrass Odyssey - A Documentary in Pictures and Words, 1966-86.

University of Illinois, Champaign, IL, 2001, ISBN 0-252-02615-2, Hardcover, 190 pp, US$34,95.

Harvey, Steven, Bound for Shady Grove.

University of Georgia Press, Athens, 2000, ISBN 0-8203-2197-4, Hardcover, 157 pp, US$24.95.

Malone, Bill C., Don't Get above Your Raisin' - Country Music and the Southern Working Class.

University of Illinois, Champaign, IL, 2002, ISBN 0-252-02678-0, Hardcover, 392 pp, US$34,95.

O Brother-Links:

Movie & Soundtrack,

Down from the Mountain,

Lyrics

Black and white photographs are taken from "Bluegrass Odyssey".

Back to the content of FolkWorld Features

To the content of FolkWorld No. 23

© The Mollis - Editors

of FolkWorld; Published 9/2002

All material published in FolkWorld is © The

Author via FolkWorld. Storage for private use is allowed and welcome. Reviews

and extracts of up to 200 words may be freely quoted and reproduced, if source

and author are acknowledged. For any other reproduction please ask the Editors

for permission. Although any external links from FolkWorld are chosen with greatest

care, FolkWorld and its editors do not take any responsibility for the content

of the linked external websites.

FolkWorld - Home of European Music

Layout & Idea of FolkWorld © The

Mollis - Editors of FolkWorld

"No one

knows how--or where--our songs began. As Indo-European tribes migrated out of

the Caucasus, they must have brought the thunder and crack and rain of their

words and songs with them into the northern reaches of the European continent.

Folk music came across the Northern Sea to the coast of England on the lips

of Anglo-Saxon warriors in the fifth century. Eventually the songs spread everywhere

in the British Isles, though the stronghold for singing remained the point of

entry, the northern borderlands where the Angles had first settled, the `north

countreye' of so many ballads."

"No one

knows how--or where--our songs began. As Indo-European tribes migrated out of

the Caucasus, they must have brought the thunder and crack and rain of their

words and songs with them into the northern reaches of the European continent.

Folk music came across the Northern Sea to the coast of England on the lips

of Anglo-Saxon warriors in the fifth century. Eventually the songs spread everywhere

in the British Isles, though the stronghold for singing remained the point of

entry, the northern borderlands where the Angles had first settled, the `north

countreye' of so many ballads."  You can, says the dulcimer player Kevin Roth, start

the scale anywhere, making this the promiscuous tuning, so easy to play that

anything goes.

You can, says the dulcimer player Kevin Roth, start

the scale anywhere, making this the promiscuous tuning, so easy to play that

anything goes.

Since the days of Andrew Jackson, and at least to 1968 or so, the majority of the white plain folk tended to be Democratic. They valued hard work and those who struggled and survived against adversity; they were suspicious of monopolies and nonproducers--bankers, lawyers, speculators, or, at the other end of the spectrum, people who lived on welfare or who otherwise lived off the labor of others. Southern working folk were usually warm, comforting, and hospitable to those who lived within or who fit the social confines of their circle of familiarity. They were prejudiced against strangers or outsiders, non-Christians, foreigners, blacks, gays, or social deviants.

Since the days of Andrew Jackson, and at least to 1968 or so, the majority of the white plain folk tended to be Democratic. They valued hard work and those who struggled and survived against adversity; they were suspicious of monopolies and nonproducers--bankers, lawyers, speculators, or, at the other end of the spectrum, people who lived on welfare or who otherwise lived off the labor of others. Southern working folk were usually warm, comforting, and hospitable to those who lived within or who fit the social confines of their circle of familiarity. They were prejudiced against strangers or outsiders, non-Christians, foreigners, blacks, gays, or social deviants.

It's hard work, yet they seem to be relaxed and happy.

The lyrics often tell sad stories at toe-tapping or breakneck speed.

It's hard work, yet they seem to be relaxed and happy.

The lyrics often tell sad stories at toe-tapping or breakneck speed.

This original country sound first flowered during the Depression. It was fertilized by blues,

gospel, string-band hoedowns, Appalachian balladry, work songs and

vaudeville hokum. Its practitioners were small-time entertainers who led

itinerant lives as they traveled from one schoolhouse show to the next,

from one radio barn dance to the next, from one makeshift recording

studio to another.

Despite the hard economic times, record companies and radio stations

discovered an enormous hunger for the homey sounds of The Carter Family,

the rowdy blues of Jimmie Rodgers, the saucy humor of Uncle Dave Macon,

the dazzling fiddling of Arthur Smith and the scintillating blues moans

of countless slide guitarists, harmonica men and jug-band songsters. That

hunger for emotional truth gave us our multi-million dollar music

industry.

The razzmatazz of western swing, the whipped-dog whine of honky-tonk

music, the creamy crooning of singing cowboys, the itchy-pants yelp of

rockabilly and the suburban gleam of The Nashville Sound seemed to drown

out the innocence of this rustic, acoustic kind of country. But it has

survived. Now called "old-time music" this style thrives at the more than

500 bluegrass festivals, fiddle contests and folk gatherings that are

staged every year in America.

You won't hear it on country radio. And it flies beneath the commercial

radar of most record shops. So for those whose musical tastes are shaped

by the great, gray behemoth that is the modern entertainment business,

this music does sound obscure. Even exotic.

The reason for our using so much of the era's music in the movie was

simple, explains Ethan Coen. We have always liked it. The mountain

music, the delta blues, gospel, the chain-gang chants, would later evolve

into bluegrass, commercial country music and rock 'n' roll. But it is

compelling music in its own right, harking back to a time when music was

a part of everyday life and not something performed by celebrities. That

folk aspect of the music both accounts for its vitality and makes it fold

naturally into our story without feeling forced or theatrical.

(

This original country sound first flowered during the Depression. It was fertilized by blues,

gospel, string-band hoedowns, Appalachian balladry, work songs and

vaudeville hokum. Its practitioners were small-time entertainers who led

itinerant lives as they traveled from one schoolhouse show to the next,

from one radio barn dance to the next, from one makeshift recording

studio to another.

Despite the hard economic times, record companies and radio stations

discovered an enormous hunger for the homey sounds of The Carter Family,

the rowdy blues of Jimmie Rodgers, the saucy humor of Uncle Dave Macon,

the dazzling fiddling of Arthur Smith and the scintillating blues moans

of countless slide guitarists, harmonica men and jug-band songsters. That

hunger for emotional truth gave us our multi-million dollar music

industry.

The razzmatazz of western swing, the whipped-dog whine of honky-tonk

music, the creamy crooning of singing cowboys, the itchy-pants yelp of

rockabilly and the suburban gleam of The Nashville Sound seemed to drown

out the innocence of this rustic, acoustic kind of country. But it has

survived. Now called "old-time music" this style thrives at the more than

500 bluegrass festivals, fiddle contests and folk gatherings that are

staged every year in America.

You won't hear it on country radio. And it flies beneath the commercial

radar of most record shops. So for those whose musical tastes are shaped

by the great, gray behemoth that is the modern entertainment business,

this music does sound obscure. Even exotic.

The reason for our using so much of the era's music in the movie was

simple, explains Ethan Coen. We have always liked it. The mountain

music, the delta blues, gospel, the chain-gang chants, would later evolve

into bluegrass, commercial country music and rock 'n' roll. But it is

compelling music in its own right, harking back to a time when music was

a part of everyday life and not something performed by celebrities. That

folk aspect of the music both accounts for its vitality and makes it fold

naturally into our story without feeling forced or theatrical.

(