Exposing a hidden history of the Caucasus mountains, Deniz Mahir Kartal, Mikail Yakut and Arsen Petrosyan

have pieced together the joint musical threads of Armenia, Georgia, Azerbaijan and Turkey.

Meet up with the A.G.A Trio...

The music of Armenia (Armenian: հայկական երաժշտություն haykakan yerazhshtut’yun) has its origins in the Armenian Highlands, dating back to the 3rd millennium BCE, and is a long-standing musical tradition that encompasses diverse secular and religious, or sacred, music (such as the sharakan Armenian chant and taghs, along with the indigenous khaz musical notation). Folk music was notably collected and transcribed by Komitas Vardapet, a prominent composer and musicologist, in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, who is also considered the founder of the modern Armenian national school of music. Armenian music has been presented internationally by numerous artists, such as composers Aram Khachaturian, Alexander Arutiunian, Arno Babajanian, Haig Gudenian, and Karen Kavaleryan as well as by traditional performers such as duduk player Djivan Gasparyan.

Traditional Armenian folk music as well as Armenian church music is not based on the European tonal system but on a system of tetrachords. The last note of one tetrachord also serves as the first note of the next tetrachord – which makes a lot of Armenian folk music more or less based on a theoretically endless scale.

Armenia has had a long tradition of folk music since antiquity. During the Soviet era, Armenian folk music was taught in state-sponsored conservatoires — in 1978, influential kanon player and composer Khachatur Avetisyan founded the folk music department of the Komitas State Conservatory of Yerevan. Traditional instruments include the qamancha, kanon (box zither), dhol (double-headed hand drum, see davul), oud (lute), duduk, zurna, blul, sring, shvi, pku, parkapzuk, tar, dmblak, bambir, and to a lesser degree the saz. Other instruments often used include the violin and clarinet. The duduk is considered to be Armenia's national instrument, and among its well-known performers are Margar Margaryan, Levon Madoyan, Vache Hovsepyan, Gevorg Dabaghyan, and Yeghish Manukyan, as well as Armenia's most famous contemporary duduk player, Djivan Gasparyan.

Notable performers of folk music include vocalists such as Armenak Shahmuradyan, Ofelya Hambardzumyan, Vagharshak Sahakyan, Araksia Gyulzadyan, Varduhi Khachatryan, Norayr Mnatsakanyan, Hovhannes Badalyan, Hayrik Muradyan, Valya Samvelyan, Rima Saribekyan, Raffi Hovhannisyan, Avak Petrosyan, Papin Poghosyan, and Flora Martirosian.

There are also several Armenian folk ensembles, the Shoghaken Folk Ensemble, founded in 1995 in Yerevan, and others such as the Arev Armenian Folk Ensemble.

In ancient and medieval Armenia, the gusans (Armenian: գուսան) were the creative and performing artists - singers, instrumentalists, dancers, storytellers, and professional folk actors in public theaters. The word gusan is first mentioned in early Armenian texts of V c., e.g. Faustus of Byzantium, Moses of Chorene, and others. In the early Middle Ages the word gusan was used as an equivalent to the classical Greek word mimos (mime). There were 2 groups of gusans:

1. The first were from aristocratic dynasties (feudal lords) and performed as professional musicians;

2. The second group comprised popular, but illiterate gusans.

The gusans were both criticized and praised, particularly in medieval Armenia. The adoption of Christianity had its influence upon Armenian minstrelsy, gradually altering its ethical and ideological orientation. The center of the gusans was the Goghtn gavar (canton), a region in the Vaspurakan province of Greater Armenia that bordered the province of Syunik.

During the late Middle Ages, gusans were succeeded by popular, semi-professional musicians called ashughs (Armenian: աշուղ), who played instruments like the kamancha and saz. Sayat-Nova, an 18th-century ashugh and poet, is revered in Armenia. Other Armenian ashughs include Jivani, Sheram, Shirin, Shahen, Havasi, and Ashot

Descendants of survivors of the Armenian Genocide, originally from Western Armenia, and Armenian emigrants from other parts of the Middle East have settled in various countries, especially in the California Central Valley. The second- and third-generation artists, such as Richard Hagopian, an oud-player associated with the kef tradition of Armenian-American music have kept their folk traditions alive. This dance-oriented style of Armenian music, using Armenian and Middle Eastern folk instruments (often electrified/amplified) and some Western instruments, preserved the folk songs and dances of Western Armenia. Many artists also played the contemporary popular songs of cosmopolitan Turkey and other Middle Eastern countries from which the Armenians emigrated (termed surjaran or café aman, meaning cafeteria), on the Eight Avenue of Manhattan, New York City. Bands such as the Vosbikian Band of Philadelphia were notable in the 1940s and 1950s for developing their own style of "kef music", heavily influenced by the popular American big band jazz of the time. Another oud player, John Berberian, is notable in particular for his fusions of traditional music with rock and jazz in the 1960s.

In the Lebanese and Syrian diaspora, George Tutunjian, Karnig Sarkissian and others performed Armenian revolutionary songs, which quickly became popular among the Armenian Diaspora, notably ARF supporters. In Tehran, Iran, the folk music of the Armenian community is characterized by the work of Nikol Galanderian (1881–1946) and the Goghtan Choir.

Armenian religious (or sacred) music, which is predominantly vocal, is one of the oldest branches of Christian culture, and was introduced after the Christianization of Armenia in 301 AD. Armenian chant, composed in one of eight modes, is the most common kind of religious music in Armenia. It is written in khaz, a form of indigenous musical notation. Many of these chants are ancient in origin, extending to pre-Christian times, while others are relatively modern, including several composed by Saint Mesrop Mashtots, who also invented the Armenian alphabet. Some of the best performers of these chants, or sharakans, reside at the Holy Cathedral of Etchmiadzin, and include the late soprano Lusine Zakaryan.

Makar Yekmalyan (1856-1905) composed the Patarag, the setting of the Armenian Apostolic Church's Divine Liturgy, which he completed in 1892 in several arrangements and was first published in Leipzig in 1896. This arrangement of the liturgy incorporated polyphonic and homophonic vocal parts into the structure of the Liturgy and saw it be notated in its entirety. This would influence the compositional approach of Komitas, who was Yekmalian's student (along with the works of Kristapor Kara-Murza) and would also see him introduce polyphony with his version of the Liturgy at the end of the 19th century.

Georgia has rich and still vibrant traditional music, which is primarily known as arguably the earliest polyphonic tradition of the Christian world. Situated on the border of Europe and Asia, Georgia is also the home of a variety of urban singing styles with a mixture of native polyphony, Middle Eastern monophony and late European harmonic languages. Georgian performers are well represented in the world's leading opera troupes and concert stages.

The folk music of Georgia consists of at least fifteen regional styles, known in Georgian musicology and ethnomusicology as "musical dialects". According to Edisher Garaqanidze, there are sixteen regional styles in Georgia. These sixteen regions are traditionally grouped into two, eastern and western Georgian groups.

The Eastern Georgian group of musical dialects consists of the two biggest regions of Georgia, Kartli and Kakheti (Garakanidze united them as "Kartli-Kakheti"); several smaller north-east Georgian mountain regions, Khevsureti, Pshavi, Tusheti, Khevi, Mtiuleti, Gudamakari; and a southern Georgian region, Meskheti. Table songs from Kakheti in eastern Georgia usually feature a long drone bass with two soloists singing the top two parts. Perhaps the best-known example of music in Kakhetian style is the patriotic "Chakrulo", which was chosen to accompany the Voyager spacecraft in 1977. Known performers from the north-eastern region Khevsureti are the singers Dato Kenchiashvili and Teona Qumsiashvili (-2012).

The Western Georgian group of musical dialects consists of the central region of western Georgia, Imereti; three mountainous regions, Svaneti, Racha and Lechkhumi; and three Black Sea coastal regions, Samegrelo, Guria, and Achara. Georgian regional styles of music are sometimes also grouped into mountain and plain groups. Different scholars (Arakishvili, Chkhikvadze, Maisuradze) distinguish musical dialects differently, for example, some do not distinguish Gudamakari and Lechkhumi as separate dialects, and some consider Kartli and Kakheti to be separate dialects. Two more regions, Saingilo (in the territory of Azerbaijan) and Lazeti (in the territory of Turkey) are sometimes also included in the characteristics of Georgian traditional music.

Georgian folk music is predominantly vocal and is widely known for its rich traditions of vocal polyphony. It is widely accepted in contemporary musicology that polyphony in Georgian music predates the introduction of Christianity in Georgia (beginning of the 4th century AD). All regional styles of Georgian music have traditions of vocal a cappella polyphony, although in the most southern regions (Meskheti and Lazeti) only historical sources provide the information about the presence of vocal polyphony before the 20th century.

Vocal polyphony based on ostinato formulas and rhythmic drone are widely distributed in all Georgian regional styles. Apart from these common techniques, there are also other, more complex forms of polyphony: pedal drone polyphony in Eastern Georgia, particularly in Kartli and Kakheti table songs (two highly embellished melodic lines develop rhythmically free on the background of pedal drone), and contrapuntal polyphony in Achara, Imereti, Samegrelo, and particularly in Guria (three and four part polyphony with highly individualized melodic lines in each part and the use of several polyphonic techniques). Western Georgian contrapuntal polyphony features the local variety of the yodel, known as krimanchuli.

Both east and west Georgian polyphony is based on wide use of sharp dissonant harmonies (seconds, fourths, sevenths, ninths). Because of the wide use of the specific chord consisting of the fourth and a second on top of the fourth (C-F-G), the founder of Georgian ethnomusicology, Dimitri Arakishvili called this chord the "Georgian Triad". Georgian music is also known for colorful modulations and unusual key changes.

Georgian polyphonic singing was among the first on the list of Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity in 2001. Georgian polyphonic singing was relisted on the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2008. It was inscribed on the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Georgia registry in 2011.

There are different, sometimes conflicting views on the nature of Georgian scales. The most prevalent is the view expressed by Vladimer Gogotishvili, who suggested distinguishing diatonic scales based on a system of perfect fourths and those based on a system of perfect fifths. A system based on perfect fourths is mostly present in Eastern Georgia, but scales based on perfect fifths are spread wider, both in eastern and particularly western Georgia, as well as in Georgian Christian chants. In East Georgian table songs the scale system is based on a combination of the systems of fourth and fifth diatonic scales. In such songs the principle of the fourth diatonic scale is working above the pedal drone, and the system of the fifth diatonic is working under the pedal drone. Because of the peculiarity of the scale system based on perfect fifths, there is often an augmented octave in Georgian songs and church-songs. As in many traditional musical systems, tuning of Georgian scales is not based on the Western classical equally tempered 12-tone tuning system. The fifth is usually perfect, but the second, third and fourth are different from Classical intervals, producing a slightly compressed (compared to most European music) major second, a neutral third, and a slightly stretched fourth. Likewise, between the fifth and the octave come two evenly spaced notes, producing a slightly compressed major sixth and a stretched minor seventh.

Because of the strong influence of Western European music, present-day performers of Georgian folk music often employ Western tuning, bringing the seconds, fourths, sixths, and sevenths, and sometimes the thirds as well, closer to the standard equally tempered scale. This process started from the very first professional choir, organized in Georgia in 1886 (so called "Agniahsvili choro"). From the 1980s some ensembles (most notably the Georgian ensembles "Mtiebi" and "Anchiskhati", and the American ensemble Kavkasia) have tried to re-introduce the original non-tempered traditional tuning system. In some regions (most notably in Svaneti) some traditional singers still sing in the old, non-tempered tuning system.

Singing is mostly a community activity in Georgia, and during big celebrations (for example, weddings) all the community is expected to participate in singing. Traditionally, top melodic parts are performed by individual singers, but the bass can have dozens or even hundreds of singers. There are also songs (usually more complex) that require a very small number of performers. Out of them the tradition of "trio" (three singers only) is very popular in western Georgia, particularly in Guria.

Georgian folk songs are often centered around banquet-like feasts called supra, where songs and toasts to God, peace, motherland, long life, love, friendship and other topics are proposed. Traditional feast songs include "Zamtari" ("Winter"), which is about the transient nature of life and is sung to commemorate ancestors, and a great number of "Mravalzhamier" songs. As many traditional activities greatly changed their nature (for example, working processes), the traditional feast became the harbor for many different genres of music. Work songs are widespread in all regions. The orovela, for example is a specific solo work song found in eastern Georgia only. The extremely complex three and four part working song naduri is characteristic of western Georgia. There are a great number of healing songs, funerary ritual songs, wedding songs, love songs, dance songs, lullabies, traveling songs. Many archaic songs are connected to round dances.

Contemporary Georgian stage choirs are generally male, though some female groups also exist; mixed-gender choirs are rare, but also exist. (An example of the latter is the Zedashe ensemble, based in Sighnaghi, Kakheti.) At the same time, in village ensembles mixed participation is more common, and according to Zakaria Paliashvili, in the most isolated region of Georgia, Upper Svaneti, mixed performance of folk songs were a common practice.

Georgian vocal polyphony was maintained for millennia by village singers, mostly local farmers. From the end of the 19th century to the beginning of the 20th century a great number of gramophone recordings of Georgian village singers were made. Anzor Erkomaishvili was paramount in recovering these recordings and re-issuing them on a series of CDs. Despite the poor technical quality of the old recordings, they often serve as the model of high mastery of the performance of Georgian traditional songs for contemporary ensembles.

During the Soviet period (1921–1991), folk music was highly praised, and revered folk musicians were awarded with governmental prizes and were given salaries. At the same time some genres were forbidden (particularly Christian church-songs), and the tendency to create huge regional choirs with big groups singing each melodic part damaged the improvisatory nature of Georgian folk music. Also, singing and dancing, usually closely interconnected in rural life, were separated on a concert stage. From the 1950s and the 1960s new type of ensembles (Shvidkatsa, Gordela) brought back the tradition of smaller ensembles and improvisation.

Since the 1970s, Georgian folk music has been introduced to a wider audience in different countries around the world. The ensembles Rustavi and later Georgian Voices were particularly active in presenting rich polyphony of various regions of Georgia to western audiences. Georgian Voices performed alongside Billy Joel, and the Rustavi Choir was featured on the soundtrack to Coen Brothers' film, The Big Lebowski. During the end of the 1960s and 1970s an innovative pop-ensemble Orera featured a mixture of traditional polyphony with jazz and other popular musical genres, becoming arguably the most popular ensemble of the Soviet Union in the 1970s. This line of fusion of Georgian folk polyphony with other genres became popular in the 1990s, and the Stuttgart-based ensemble The Shin became a popular representative of this generation of Georgian musicians.

By the mid-1980s, the first ensembles of Georgian music consisting of non-Georgian performers had started to appear outside of Georgia (first in USA and Canada, later in other European countries). This process became particularly active after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, when the iron curtain disappeared and travel to the Western countries became possible for Georgians. Today it is a common practice for Georgian ensembles and traditional singers to visit Western countries for performances and workshops.

A wide variety of musical instruments are known from Georgia. Among the most popular instruments are: blown instruments soinari, known in Samegrelo as larchemi (Georgian panpipe), stviri (flute), gudastviri (bagpipe), sting instruments changi (harp), chonguri (four stringed unfretted long neck lute), panduri (three stringed fretted long neck lute), bowed chuniri, known also as chianuri, and variety of drums. Georgian musical instruments are traditionally overshadowed by the rich vocal traditions of Georgia, and subsequently received much less attention from Georgian (and Western) scholars. Dimitri Arakishvili and particularly Manana Shilakadze contributed to the study of musical instrument in Georgia.

Only the mountain inhabitants of Georgia preserve the bowed Chuniri in its original form. This instrument is considered to be a national instrument of Svaneti and is thought to have spread in the other regions of Georgia from there. Chuniri has different names in different regions: in Khevsureti, Tusheti (Eastern mountainous parts) its name is Chuniri, and in Racha, Guria (western parts of Georgia) "Chianuri". Chuniri is used for accompaniment. It is often played in an ensemble with Changi (harp) and Salamuri (flute). Both men and women played it. Accompaniment of solo songs, national heroic poems and dance melodies were performed on it in Svaneti. Chuniri and Changi are often played together in an ensemble when performing polyphonic songs. More than one Chianuri at a time is not used. Chianuri is kept in a warm place. Often, especially in rainy days it was warmed in the sun or near fireplace before using, in order to emit more harmonious sounds. This fact is acknowledged in all regions where the fiddlestick instruments were spread. That is done generally because dampness and wind make a certain effect on the instrument's resonant body and the leather that covers it. In Svaneti and Racha people even could make a weather forecast according to the sound produced by Chianuri. Weak and unclear sounds were the signs of a rainy weather. The instrument's side strings i.e. first and third strings are tuned in fourth, but the middle (second) string is tuned in third with the lowest string and second with the top string. It was a tradition to play Chuniri late in the evening the day before a funeral. For instance, one of the relatives (man) of a dead person would sit down in open air by the bonfire and play a sad melody. In his song (sang in a low voice) he would remember the life of the deceased person and the lives of ancestors of the family. Most of the songs performed on Chianuri are connected with sad occasions. There is an expression in Svaneti that "Chuniri is for sorrow". However, it can be used at parties as well.

The Abkharza is a two-string musical instrument which is played by a bow. It is thought to have spread through Georgia from the region of Abkhazia. Mostly the Abkharza is used as an accompaniment instrument. There are performed one, two or three part songs and national heroic poems on it. Abkharza is cut out of a whole wood piece and has a shape of a boat. Its overall length is 480mm. its upper board is glued back to the main part. On the end it has two tuners.

Azerbaijani music (Azerbaijani: Azərbaycan musiqisi) is the musical tradition of the Azerbaijani people from Azerbaijan Republic. It builds on folk traditions that reach back nearly 1,000 years. For centuries, Azerbaijani music has evolved under the badge of monody, producing rhythmically diverse melodies. Music from Azerbaijan has a branch mode system, where chromatisation of major and minor scales is of great importance.

Most songs recount stories of real life events and Azerbaijani folklore, or have developed through song contests between troubadour poets. Corresponding to their origins, folk songs are usually played at weddings, funerals and special festivals.

Regional folk music generally accompanies folk dances, which vary significantly across regions. The regional mood also affects the subject of the folk songs, e.g. folk songs from the Caspian Sea are lively in general and express the customs of the region. Songs about betrayal have an air of defiance about them instead of sadness, whereas the further south travelled in Azerbaijan the more the melodies resemble a lament.

As this genre is viewed as a music of the people, musicians in socialist movements began to adapt folk music with contemporary sounds and arrangements in the form of protest music.

Instruments used in traditional Azerbaijani music include the stringed instruments tar (skin faced lute), the kamancha (skin faced spike fiddle), the oud, originally barbat, and the saz (long necked lute); the double-reed wind instrument balaban, the frame drum ghaval, the cylindrical double faced drum nagara (davul), and the gosha nagara (pair of small kettle drums). Other instruments include the garmon (small accordion), tutek (whistle flute), and daf (frame drum).

Due to the cultural crossbreeding prevalent during the Ottoman Empire, the tutek has influenced various cultures in the Caucasus region, e.g. the duduks. The zurna and naghara duo is also popular in rural areas, and played at weddings and other local celebrations.

Ashiqs are travelling bards who sing and play the saz, a form of lute. Their songs are semi-improvised around a common base. This art is one of the symbols of Azerbaijani culture and considered an emblem of national identity and the guardian of Azerbaijani language, literature and music.

Characterized by the accompaniment of the kopuz, a stringed musical instrument, the classical repertoire of Azerbaijani Ashiqs includes 200 songs, 150 literary-musical compositions known as dastans, nearly 2,000 poems and numerous stories.

Since 2009 the art of Azerbaijani Ashiqs has been inscribed on the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

Meykhana is a distinctive Azerbaijani literary and folk rap tradition, consisting of an unaccompanied song performed by one or more people improvising on a particular subject. Meykhana is distinct from spoken word poetry in that it is performed in time to a beat.

Meykhana is often compared to hip hop music, also known as national rap among Azerbaijani residents, as it also includes performers that is spoken lyrically, in rhyme and verse, generally to an instrumental or synthesized beat. Performers also incorporate synthesizers, drum machines, and live bands. Meykhana masters may write, memorize, or improvise their lyrics and perform their works a cappella or to a beat.

Mugham is one of the many folk musical compositions from Azerbaijan, contrast with Tasnif, Ashugs. Mugam draws on Arabic maqam.

It is a highly complex art form that weds classical poetry and musical improvisation in specific local modes. Mugham is a modal system. Unlike Western modes, "mugham" modes are associated not only with scales but with an orally transmitted collection of melodies and melodic fragments that performers use in the course of improvisation. Mugham is a compound composition of many parts. The choice of a particular mugham and a style of performance fits a specific event. The dramatic unfolding in performance is typically associated with increasing intensity and rising pitches, and a form of poetic-musical communication between performers and initiated listeners.

Three major schools of mugham performance existed from the late 19th and early 20th centuries - the region of Garabagh, Shirvan, and Baku. The town of Shusha of Karabakh was particularly renowned for this art.

The short selection of Azerbaijani mugham played in balaban, national wind instrument was included on the Voyager Golden Record, attached to the Voyager spacecraft as representing world music, included among many cultural achievements of humanity.

In 2003, UNESCO proclaimed mugham as a Masterpiece of Oral and Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License.

Date: October 2020.

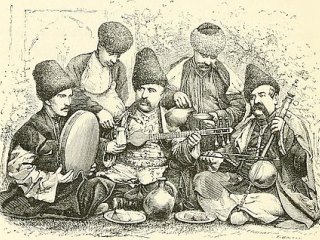

Photo Credits:

(1) Caucasus,

(2)-(6) A.G.A Trio,

(7)-(8),(13) Armenia,

(9) Arto Tunçboyacıyan,

(10)-(11) Georgia,

(12) Alan Shavarsh Bardezbanian,

(14) The Shin,

(15) Vardan Hovanissian & Emre Gültekin,

(16)-(17) Azerbaijan,

(18) Turkey,

(19) Gochag Askarov,

(20) Miqayel Voskanyan and Friends (MVF Band)

(unknown/website).