Songs That Made History: Although by the spring of 1792 the French Revolution was well under way, there had, so far, arisen no song which had made history. It is true that in the streets of Paris they had been singing.

Ah ça ira ça ira ça ira. Les aristocrat' à la lanterne.

There were also La Carmagnole and other songs; these were ferocious, but little else. On 20th April of that year, the French Legislature formally declared war on Germany and Austria. Four days later, on 24th April, there was an evening party at the house of Baron Dietrich, Mayor of Strasbourg. All day, soldiers had been marching into the city to join the army of the Rhine. At the Dietrichs' party, conversation turned on their songs–the illiteracy and grossness of the words, and the lack of distinction in the music. Among the guests was a young captain of engineers, Rouget de Lisle, known to be a poet and an amateur musician. Turning to him, the mayor said, in effect: 'Captain, you ought to write us a war-song.' This suggestion was warmly supported by Madame Dietrich, herself an able musician, and by the other guests.

After the party, Rouget de Lisle went back to his lodgings, doubtless with brain on fire with thoughts of war and of Liberty. Taking up his violin, he began to play. In a few hours he had forged tune and six verses of the song now known as La Marseillaise. Next forenoon he took his rough MS. to Madame Dietrich. She copied the tune and made a harpsichord accompaniment to it. The same evening it was sung by the mayor, who possessed a fine tenor voice.

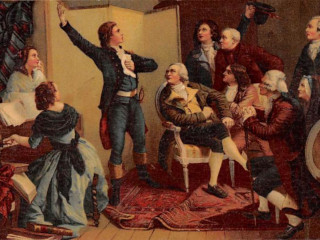

It has been said, more than once, that Rouget de Lisle did not compose the tune, that he compiled it from well-known marches, that it was a German folk-song–of all impossible things–and so on. None of these theories has been shown to have any foundation. The account given above, which seems to place the matter beyond doubt, is based on a letter written a few days later by Madame Dietrich to her brother living at Basle and quoted in an article in L'Illustration for 20th June 1936. There is a well-known picture by Pils representing Rouget de Lisle singing La Marseillaise for the first time in the salon of the mayor's house. There are other pictures representing the same event. A beautiful one by Godfroid Guffens, from the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, is reproduced as the frontispiece to this book. But the 'event' was imaginary; for it seems certain that it was the mayor himself who sang the song for the first time, not the composer.

Within a few days the tune was arranged for military band and was played in public. Yet it did not become popular at once. It was not until, a month later, it was sung by a professional singer at a banquet at Marseilles that it made a 'hit.' Then the effect was so tremendous that copies of the words were struck off and distributed to the levies who were about to march to Paris. They entered Paris on 30th July, singing the song, and in August they advanced to the attack on the Tuileries to its strains. So the song changed its name. It was known no longer as Chant de guerre pour l'armée du Rhin, but as La chant marseillaise and then, simply as La Marseillaise.

In its earliest days the tune had been harmonized and 'arranged' by Madame Dietrich and others. Now, famous musicians took it in hand: Grétry enriched its harmonies; it has been scored for full orchestra with all brilliance by Hector Berlioz. [...] A study of [Rouget de Lisle's original version] indicates how words and music took form together; the sharp dissonance at 'mugir' is noteworthy–it is softened in its present form; the trumpet-call is a perfect fit to the words 'Aux armes, Citoyens.' It will be observed that the tune has been slightly modified, that 'Marchez' has been altered to 'Marchons,' and that later editors have wisely expunged the rather meaningless and totally unnecessary fanfare between the verses.

Allons enfants de la Patrie,

Le jour de gloire est arrivé;

Contre nous de la tyrannie

L’étendard sanglant est levé.

Entendez-vous dans les campagnes

Mugir ces féroces soldats?

Ils viennent jusque dans vos bras

Égorger vos fils–vos compagnes!

Aux armes Citoyens!

Formez vos bataillons,

Marchez, Marchez,

Qu’un sang impur

Abreuve nos sillons!

It is impossible to pretend that the words are good poetry. But they are interesting and impressive in that they reflect the occasion and are so obviously born of the emotion of the moment. At his party, the mayor had told his guests that his son was in command of a battalion of recruits whom he had christened 'Enfants de la Patrie.' This gave Rouget de Lisle his first line. Other lines were worked up from tags from the proclamations he had read posted up in the city that day: 'Le jour de gloire est arrivé,' 'Aux armes, citoyens, formez vos bataillons,' 'Tremblez, tyrans.' The best verse of La Marseillaise was not written by de Lisle. It is that known as 'the children's verse.' It was added by Dubois for recital by a child at the Fête de la Fédération:

Nous entrerons dans la carrière, Quand nos aînés n’y seront plus; Nous y trouverons leur poussière Et la trace de leurs vertus. Bien moins jaloux de leur survivre Que de partager leur cercueil, Nous aurons le sublime orgueil De les venger ou de les suivre.

La Marseillaise soon became adopted everywhere, not only in France, as a symbol of revolt. To sing the tune in any country was to proclaim oneself as 'agin the government.' It was so infectious, so subversive, that in many countries of Europe in the first half of the nineteenth century the tune was prohibited. It was as dangerous to sing or to whistle it in the streets of Vienna in 1838 as it would be to whistle or to sing L'Internationale in certain cities of Europe to-day. Schumann turned this nervousness of the Viennese police to comic use. He had been irritated by the red-tape of the authorities when he wanted to publish a musical journal in Vienna a few years before. So in 1838 he composed and played there a pianoforte piece called Faschingsschwank aus Wien (Carnival Jest at Vienna). In this there suddenly dances across the stage, as it were, a wraith, a caricature, of the forbidden tune. The tune had a peculiar fascination for Schumann. He uses it also in an overture: and, with splendid effect, in the final verse of his well-known setting of Die beiden Grenadiere.

La Marseillaise is no longer the symbol of revolt, the anthem of the extreme left wing; its place has been taken by L'Internationale. It is, of course, the national anthem of the French Republic. Its tune has many admirers. There is something very determined about the way it leaps on to the high note in its first phrase–this has been likened to a man drawing a sword from its sheath and flashing it in the sun. It is an illustration of the power of rhythm to alter the significance of a phrase to compare the start of this tune with the openings of two movements well known to musicians, that of the first movement of the fifth symphony of Sibelius and that of the slow movement of the 'double' concerto by Brahms. The minor section of La Marseillaise forms an admirable contrast to the martial music of the tune. [...]

In 1796 there was living in Vienna the composer Joseph Haydn. He had paid two visits to England, where he had heard and admired the tune to God save the King. By 1796 the victories of the French Revolutionary armies were exciting alarm in Vienna; everywhere these armies took with them La Marseillaise, and the tune was infectious. So Haydn conceived the idea of a national hymn which should express for Austria at this crisis what God save the King stood for in England: loyalty and attachment to the throne. He told his idea to the Prime Minister, who commissioned the court poet Hauschka to write him some verses. These Haydn set to music in 1797. He took, it is said, a Croatian national tune as a basis and remodelled it till he produced what was known as the Emperor's Hymn:

Gott erhalte Franz den Kaiser, Unsern guten Kaiser Franz.

Without the repetition of the last two phrases the tune is very well known in this country as the hymn-tune Austria.

The Great War caused many changes of national anthems. This tune is still played as the national anthem of Austria, though different words have been set to it. Before 1914, the tune was sung in Germany to the words 'Deutschland, Deutschland, über Alles,' and when it was necessary to drop Heil dir im Siegerkrantz (sung to the tune of the British national anthem) this took its place. Deutschland, Deutschland, über Alles, to Haydn's tune, is still the national anthem of Germany, though it is now followed by the Horst Wessel Song.

Haydn realized what a lovely thing his tune was, so he incorporated it in a string quartet (Op. 76, No. 3–commonly known as the Kaiser quartet). There we find the tune followed by four variations, which are among the most beautiful things in classical music. [...]

The tune of the Horst Wessel Song was popular before 1914. Like our Tipperary, it was probably a music-hall tune. It was used by the German troops as a marching song in 1914. In 1916 it was popular at Kiel, where it was sung by German sailors to some verses written to it recounting the exploits of the cruiser Königsberg, which put up a fine fight for eight months in the Rufigi river. The tune was thus well-known before 1930, when the young storm-trooper Horst Wessel wrote some words to it. The author's sudden death gave to these verses a posthumous importance, and the song was adopted as the particular anthem of the Nazi Party.

Excerpt taken from: H.E. Piggott, Songs That Made History. J.M. Dent & Sons Ltd, London, 1937.

Photo Credits:

(1) Eugène Delacroix: La Liberté guidant le peuple (1830),

(2) Isidore Pils: Rouget de Lisle chantant la Marseillaise (1849),

(3) Egide Godfried Guffens: Marseillaise (c.1870-80),

(4) Thomas Hardy: Joseph Haydn (1791)

(5) Marche des Marseillois chantée sur diferans theatres (1792)

(unknown/website);

(6) Joseph Haydn: Kaiserhymne (Colour lithograph, 19th century)

(by Österreichische Nationalbibliothek).