www.robertburns.org

homecomingscotland2009.com

www.burnssupper2009.com

www.celticconnections.com

burns.visitscotland.com

www.thegathering2009.com

FolkWorld Issue 38 03/2009; Article from Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

www.robertburns.org |

Robert Burns

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Robert Burns is widely regarded as the national poet of Scotland. As well as making original compositions, Burns collected folk songs from across Scotland, often revising or adapting them. A cultural icon in Scotland and among the Scottish Diaspora around the world, celebration of his life and work became almost a national charismatic cult during the 19th and 20th centuries.

Robert Burns (25 January 1759 – 21 July 1796) (also known as Rabbie Burns, Scotland's favourite son, the Ploughman Poet, the Bard of Ayrshire and in Scotland as simply The Bard) was a poet and a lyricist. He is widely regarded as the national poet of Scotland, and is celebrated worldwide. He is the best known of the poets who have written in the Scots language, although much of his writing is also in English and a 'light' Scots dialect, accessible to an audience beyond Scotland. He also wrote in standard English, and in these pieces, his political or civil commentary is often at its most blunt.

He is regarded as a pioneer of the Romantic movement and after his death became a great source of inspiration to the founders of both liberalism and socialism. A cultural icon in Scotland and among the Scottish Diaspora around the world, celebration of his life and work became almost a national charismatic cult during the 19th and 20th centuries, and his influence has long been strong on Scottish literature.

As well as making original compositions, Burns also collected folk songs from across Scotland, often revising or adapting them. His poem (and song) Auld Lang Syne is often sung at Hogmanay (New Year), and Scots Wha Hae served for a long time as an unofficial national anthem of the country.

Other poems and songs of Burns that remain well-known across the world today,

include A Red, Red Rose, A Man's A Man for A' That, To a Louse, To a Mouse, The Battle of Sherramuir, and Ae Fond Kiss.

Other poems and songs of Burns that remain well-known across the world today,

include A Red, Red Rose, A Man's A Man for A' That, To a Louse, To a Mouse, The Battle of Sherramuir, and Ae Fond Kiss.

Music of ScotlandScotland is internationally known for its traditional music, which has remained vibrant throughout the 20th century, when many traditional forms worldwide lost popularity to pop music. In spite of emigration and a well-developed connection to music imported from the rest of Europe and the United States, the music of Scotland has kept many of its traditional aspects; indeed, it has itself influenced many forms of music. Scottish traditional music, although both influencing and being influenced by Irish traditional music, is very much a creature unto itself, and, despite the popularity of various international pop music forms, remains a vital and living tradition. There are several Scottish record labels, music festival and a roots magazine, Living Tradition. Many outsiders associate Scottish folk music almost entirely with the Great Highland Bagpipe, which has indeed long played an important part of Scottish music. Although this particular form of bagpipe developed exclusively in Scotland, it is not the only Scottish bagpipe, and other bagpiping traditions remain across Europe. The earliest mention of bagpipes in Scotland date to the 1400s, but they could have been introduced to Scotland as early as the sixth century. The pìob mór, or Great Highland Bagpipe, was originally associated with both hereditary piping families and professional pipers to various clan chiefs; later, pipes were adopted for use in other venues, including military marching. Piping clans included the MacArthurs, MacDonalds, McKays and, especially, the MacCrimmon, who were hereditary pipers to the Clan MacLeod. Folk musicFolk music takes many forms in a broad musical tradition, although the dividing lines are not rigid, and many artists work across the boundaries. Culturally, there is a split between the Gaelic tradition and the Scots tradition. The oldest forms of music in Scotland are theorized to be Gaelic singing and harp playing. Although much of the harp tradition was lost through extinction, the harp is being revived by contemporary players. Later, the Great Highland Bagpipe appeared on the scene. Initially, pipers played traditional pieces called 'piobaireachd', meaning 'piping' in Gaelic, which consist of a theme and a series of developments. Later, the style of 'light music,' including marches, strathspeys, reels, jigs, and hornpipes, became more popular. The British army adopted piping and spread the idea of pipe bands throughout the British Empire. Presently, piping is closely tied to band and individual competitions, although pipers are also experimenting with new possibilities for the instrument. Other forms of bagpipes also exist in the Scottish tradition; they are detailed in the piping section below. The piping tradition is strongly connected to Gaelic singing (some piping ornaments mimic the Gaelic consonants of the songs), stepdance (the traditional dance meters determine the rhythm of the tunes), and fiddle, which appeared in Scotland in the 17th century. These components are part of the dance music which is played across Scotland at country dances, ceilidhs, Highland balls and frequently at weddings. Group dances are performed to music provided typically by an ensemble, or dance band, which may include fiddle, bagpipe, accordion, tin whistle, cello, keyboard and percussion. Many modern Scottish dance bands are becoming more lively and innovative, with influences from other types of music (most notably jazz chord structures) becoming noticeable. Vocal music is also popular in the Scottish musical tradition. There are ballads and laments, generally sung by a lone singer with backing, or played on traditional instruments such as harp, fiddle, accordion or bagpipes. There are many traditional folk songs, which are generally melodic, haunting or rousing. These are often very specific to certain regions, and are performed today by a burgeoning variety of folk groups. Popular songs were originally produced by music hall performers such as Harry Lauder and Will Fyffe for the stage. More modern exponents of the style have included Andy Stewart, Glen Daly, Moira Anderson, Kenneth McKellar, Calum Kennedy and the Alexander Brothers. Folk song collectingThe earliest printed collection of secular music in Scotland was by publisher John Forbes in Aberdeen in 1662. Songs and Fancies: to Thre, Foure, or Five Partes, both Apt for Voices and Viols, printed three times in the next twenty years, contained 77 songs, of which 25 were of Scottish origin. Most are anonymous. The other songs in the book are mostly in English, and include works by John Dowland. While ballads had been written for centuries, and had begun to be printed in the seventeenth century, the 18th century brought a number of collections of Scots songs and tunes. Examples include Playford's Original Scotch Tunes 1700, Sinkler's MS. 1710, James Watson's Choice Collection of Comic and Serious Scots Poems both Ancient and Modern 1711, William Thomson's Orpheus caledonius: or, A collection of Scots songs 1733, James Oswald's The Caledonian Pocket Companion 1751, and David Herd's Ancient and modern Scottish songs, heroic ballads, etc.: collected from memory, tradition and ancient authors 1776. These were drawn on for the most influential collection, The Scots Musical Museum published in six volumes from 1787 to 1803 by James Johnson and Robert Burns, which also included new words by Burns. The Select Scottish Airs collected by George Thomson and published between 1799 and 1818 included contributions from Burns and Walter Scott. InstrumentsAccordionThough often derided as Scottish kitsch, the accordion has long been a part of Scottish music. Country dance bands, such as that led by the renowned Jimmy Shand, have helped to dispel this image. In the early twentieth century, the melodeon (a variety of accordion) was popular among rural folk, and was part of the bothy band tradition. More recently, performers like Phil Cunningham (of Silly Wizard) have helped popularize the accordion in Scottish music. BagpipesThough bagpipes are closely associated with Scotland by many outsiders, the instrument (or, more precisely, family of instruments) is found throughout large swathes of Europe, North Africa and South Asia. The most common bagpipe heard in modern Scottish music is the Great Highland Bagpipe, which was spread by the Highland regiments of the British Army. Historically, numerous other bagpipes existed, and many of them have been recreated in the last half-century. The classical music of the Great Highland Bagpipe is called Pìobaireachd, which consists of a first movement called the urlar (in English, the 'ground' movement,) which establishes a theme. The theme is then developed in a series of movements, growing increasingly complex each time. After the urlar comes the taorluath movement and variation and the crunluath movement, continuing with the underlying theme. This is usually followed by the crunluath a mach; the piece closes with a return to the urlar. Bagpipe competitions are common in Scotland, for both solo pipers and pipe bands. Competitive solo piping is currently popular among many aspiring pipers, some of whom travel from as far as Australia to attend Scottish competitions. Other pipers have chosen to explore more creative usages of the instrument. Different types of bagpipes have also seen a resurgence since the 70s, as the historical border pipes and Scottish smallpipes have been resuscitated and now attract a thriving alternative piping community. The pipe band is another common format for highland piping, with top competitive bands including the Victoria Police Pipe Band from Australia (formerly), Northern Ireland's Field Marshal Montgomery, Canada's 78th Fraser Highlanders Pipe Band and Simon Fraser University Pipe Band, and Scottish bands like Shotts and Dykehead Pipe Band and Strathclyde Police Pipe Band. These bands, as well as many others, compete in numerous pipe band competitions, often the World Pipe Band Championships, and sometimes perform in public concerts. FiddleScottish traditional fiddling encompasses a number of regional styles, including the bagpipe-inflected west Highlands, the upbeat and lively style of Norse-influenced Shetland Islands and the Strathspey and slow airs of the North-East. The fiddle arrived late in the 17th century, and is first mentioned in 1680 in a document from Newbattle Abbey in Midlothian, Lessones For Ye Violin. In the 18th century, Scottish fiddling is said to have reached new heights. Fiddlers like William Marshall and Niel Gow were legends across Scotland, and the first collections of fiddle tunes were published in mid-century. The most famous and useful of these collections was a series published by Nathaniel Gow, one of Niel's sons, and a fine fiddler and composer in his own right. Classical composers such as Charles McLean, James Oswald and William McGibbon used Scottish fiddling traditions in their Baroque compositions. Scottish fiddling is the root of much American folk music, such as Appalachian fiddling, but is most directly represented in Cape Breton, Nova Scotia, an island on the east coast of Canada, which received some 25,000 emigrants from the Scottish Highlands during the Highland Clearances of 1780-1850. Cape Breton musicians such as Natalie MacMaster, Ashley MacIsaac, and Jerry Holland have brought their music to a worldwide audience, building on the traditions of master fiddlers such as Buddy MacMaster and Winston Scotty Fitzgerald. Among native Scots, Alasdair Fraser and Aly Bain are two of the most accomplished, following in the footsteps of influential twentieth century players such as James Scott Skinner, John McCusker, Hector MacAndrew, Angus Grant and Tom Anderson. The growing number of young professional Scottish fiddlers makes a complete list impossible. GuitarThe history of the guitar in traditional music is recent, as is that of the cittern and bouzouki, which in the forms used in Scottish and Irish music only date to the late 1960s. The guitar featured prominently in the folk revival of the early 1960s with the likes of Archie Fisher, the Corries, Hamish Imlach, Robin Hall and Jimmie MacGregor. The virtuoso playing of Bert Jansch was widely influential, and the range of instruments was widened by the Incredible String Band. Notable artists include Tony McManus, Dave MacIsaac, Peerie Willie Johnson and Dick Gaughan. Other notable guitarists in Scottish music scene include Kris Drever of Fine Friday and Lau, and Ross Martin of Cliar, Daimh and Harem Scarem. HarpThe harp, or clarsach, has a long and ancient history in Scotland, and was regarded as the national instrument until it was replaced with the Highland bagpipes in the 15th century. Stone carvings in the East of Scotland support the theory that the harp was present in Pictish Scotland well before the 9th century and may have been the original ancestor of the modern European harp and even formed the basis for Scottish pibroch, the folk bagpipe tradition. Only thirteen depictions exist in Europe of any triangular chordophone harp pre-11th century, and all thirteen of them come from Scotland. Pictish harps were strung from horsehair. The instruments apparently spread south to the Anglo-Saxons, who commonly used gut strings, and then west to the Gaels of the Highlands and to Ireland. The earliest Irish word for a harp is in fact Cruit, a word which strongly suggests a Pictish provenance for the instrument. The surname MacWhirter, mac a' chruiteir, means son of the harpist, and is common throughout Scotland, but particularly in Carrick and Galloway. The Clàrsach (Gd.) or Cláirseach (Ga.) is the name given to the wire-strung harp of either Scotland or Ireland. The word begins to appear by the end of the 14th century. Until the end of the Middle Ages it was the most popular musical instrument in Scotland, and harpers were among the most prestigious cultural figures in the courts of Irish/Scottish chieftains and Scottish kings and earls. In both countries, harpers enjoyed special rights and played a crucial part in ceremonial occasions such as coronations and poetic bardic recitals. The Kings of Scotland employed harpers until the end of the Middle Ages, and they feature prominently in royal iconography. Several Clarsach players were noted at the Battle of the Standard (1138), and when Alexander III (died 1286) visited London in 1278, his court minstrels were with him, payments were made to Elyas the "King of Scotland's harper." Three medieval Gaelic harps survived into the modern period, two from Scotland (the Queen Mary Harp and the Lamont Harp) and one in Ireland (the Brian Boru harp), although artistic evidence suggests that all three were probably made in the western Highlands. The playing of this Gaelic harp with wire strings died out in Scotland in the 18th century and in Ireland in the early 19th century. As part of the late 19th century Gaelic revival, the instruments used differed greatly from the old wire-strung harps. The new instruments had gut strings, and their construction and playing style was based on the larger orchestral pedal harp. Nonetheless the name "clàrsach" was and is still used in Scotland today to describe these new instruments. The modern gut-strung clàrsach has thousands of players, both in Scotland and Ireland, as well as North America and elsewhere. The 1931 formation of the Clarsach Society kickstarted the modern harp renaissance. Recent harp players include Savourna Stevenson, Maggie MacInnes, and the band Sileas. Notable events include the Edinburgh International Harp Festival, which recently staged the world record for the largest number of harpists to play at the same time. Tin whistleOne of the oldest tin whistles still in existence is the Tusculum whistle, found with pottery dating to the 14th and 15th centuries; it is currently in the collection of the Museum of Scotland. Today the whistle is a very common instrument in recorded Scottish music. Although few well-known performers choose the tin whistle as their principal instrument, it is quite common for pipers, flute players, and other musicians to play the whistle as well. Modern Scottish musicIn the twentieth century, collections like Last Leaves of Traditional Ballads and Ballad Airs, collected by Reverend James Duncan and Gavin Greig, helped inspire the ensuing folk revival. These were followed by collectors like Hamish Henderson and Calum McLean, both of whom worked with American musicologist Alan Lomax. Earlier, the first Celtic music international star, James Scott Skinner, a fiddler known as the "Strathspey King", had gained fame with some very early recordings. Among the folk performers discovered by Henderson, McLean and Lomax was Jeannie Robertson, who was brought to sing at the People's Festival in Edinburgh in 1953. Across the Atlantic, in the United States, pop-folk groups like The Weavers, Pete Seeger and Woody Guthrie were leading a folk revival; the singers at the 1951 People's Festival, John Strachan (singer), Flora Macneill, Jimmy MacBeath and others, began the Scottish revival. RevivalLike many countries, Scotland underwent a roots revival in the 1960s. Folk music had declined somewhat in popularity during the preceding generation, although performers like Jimmy Shand, Kenneth McKellar, and Moira Anderson still maintained an international following and mass market record sales, but numerous young Scots thought themselves separated from their country's culture. This new wave of Scottish folk performers were inspired by American traditionalists like Pete Seeger, but soon found their own heroes, including young singers Ray and Archie Fisher and Hamish Imlach, and from the tradition Jeannie Robertson and Jimmy MacBeath. 1960sScottish folk singing was revived by artists including Ewan MacColl, who founded one of the first folk clubs in Britain, singers Alex Campbell, Jean Redpath, Hamish Imlach, and Dick Gaughan and groups like The Gaugers, The Corries, The McCalmans and the Ian Campbell Folk Group. Folk clubs boomed, with a strong Irish influence from The Dubliners. With Irish folk bands like The Chieftains finding widespread popularity, 60s Scottish musicians played in pipe bands and Strathspey and Reel Societies. Musicologist Frances Collinson published The Traditional and National Music of Scotland in 1966 to surprising popular acclaim, as part of the burgeoning Scottish folk revival. Still though, until the end of the 60s, Scottish music was rarely heard in pubs or on the radio, though Irish traditional music was widespread. The Corries had established a fan-base, while the English band Fairport Convention has created a British folk rock scene that spread north in the form of JSD Band and Contraband. A more conventional approach was taken by Andy Stewart, Glen Daly and The Alexander Brothers. 1970sMusic had long been primarily a solo affair, until The Clutha, a Glasgow-based group, began solidifying the idea of a Celtic band, which eventually consisted of fiddle or pipes leading the melody, and bouzouki and guitar along with the vocals. Though The Clutha were the first modern band, earlier groups like The Exiles (with Bobby Campbell) had forged in that direction, adding instruments like the fiddle to vocal groups. Alongside The Clutha were other pioneering Glasgow bands, including The Whistlebinkies and Aly Bain's The Boys of the Lough, both largely instrumental. The Whistlebinkies were notable, along with Alba and The Clutha, for experimenting with different varieties of bagpipies; Alba used Highland pipes, The Whistlebinkies used reconstructed Border pipes and The Clutha used Scottish smallpipes alongside Highlands. Bert Jansch and Davy Graham took blues guitar and eastern influences into their music, and in the mid-1960s, the most popular group of the Scottish folk scene, the Incredible String Band, began their career in Clive's Incredible Folk Club in Glasgow taking these influences a stage further. The next wave of bands, including Silly Wizard, The Tannahill Weavers, Battlefield Band, Ossian and Alba, featured prominent bagpipers, a trend which climaxed in the 1980s, when Robin Morton's A Controversy of Pipers was released to great acclaim. By the end of the 1970s, lyrics in the Scottish Gaelic language were appearing in songs by Nah-Oganaich and Ossian, with Runrig's Play Gaelic in 1978 being the first major success for Gaelic-language Scottish folk. 1980s, 1990s and 2000sIn the 1980s, Edinburgh saw the emergence of Jock Tamson's Bairns with a style called Scots swing. Most recently, Scottish piping has included a renaissance for cauldwind pipes such as smallpipes and border pipes, which use cold, dry air as opposed to the moist air of mouth-blown pipes. Other pipers such as Gordon Duncan and Fred Morrison began to explore new musical genres on many kinds of pipes. The accordion also gained in popularity during the 1970s due to the renown of Phil Cunningham, whose distinctive piano accordion style was an integral part of the band Silly Wizard. Numerous musicians continued to follow more traditional styles including Alex Beaton. More modern musicians include Shooglenifty, The Easy Club, a jazz fusion band, Talitha MacKenzie and Martin Swan, puirt a' bhèil mouth musicians, pioneering singers Savourna Stevenson, Heather Heywood and Christine Primrose. Other modern musicians include the late techno-piper Martyn Bennett (who used hip hop beats and sampling), Hamish Moore, Hamish Stuart, Jim Diamond, Sheena Easton and Gordon Mooney.

|

Burns was born two miles (3 km) south of Ayr, in Alloway, South Ayrshire, Scotland, the eldest of the seven children of William Burness (1721-1784) (Robert Burns spelled his surname Burness until 1786), a self-educated tenant farmer from Dunnottar, The Mearns, and Agnes Broun (1732-1820), the daughter of a tenant farmer from Kirkoswald, South Ayrshire.

He was born in a house built by his father (now the Burns Cottage Museum), where he lived until Easter 1766, when he was seven years old. William Burness sold the house and took the tenancy of the 70-acre Mount Oliphant farm, southeast of Alloway. Here Burns grew up in poverty and hardship, and the severe manual labour of the farm left its traces in a premature stoop and a weakened constitution.

He had little regular schooling and got much of his education from his father, who taught his children reading, writing, arithmetic, geography, and history and also wrote for them A Manual Of Christian Belief. He was also taught by John Murdoch (1747-1824), who opened an 'adventure school' in Alloway in 1763 and taught Latin, French, and mathematics to both Robert and his brother Gilbert (1760-1827) from 1765 to 1768 until Murdoch left the parish. After a few years of home education, Burns was sent to Dalrymple Parish School during the summer of 1772 before returning at harvest time to full-time farm labouring until 1773, when he was sent to lodge with Murdoch for three weeks to study grammar, French, and Latin.

By the age of 15, Burns was the principal labourer at Mount Oliphant. During the harvest of 1774, he was assisted by Nelly Kilpatrick (1759-1820), who inspired his first attempt at poetry, O, Once I Lov'd A Bonnie Lass. In the summer of 1775, he was sent to finish his education with a tutor at Kirkoswald, where he met Peggy Thomson (b.1762), to whom he wrote two songs, Now Westlin' Winds and I Dream'd I Lay.

At Whitsun, 1777, William Burness removed his large family from the unfavourable conditions of Mount Oliphant to the 130-acre (0.53 km2) farm at Lochlea, near Tarbolton, where they stayed until Burness's death in 1784. Subsequently, the family became integrated into the community of Tarbolton. To his father's disapproval, Robert joined a country dancing school in 1779 and, with Gilbert, formed the Tarbolton Bachelor's Club the following year. In 1781 Burns became a Freemason at Lodge St David, Tarbolton. His earliest existing letters date from this time, when he began making romantic overtures to Alison Begbie (b. 1762). In spite of four songs written for her and a suggestion that he was willing to marry her, she rejected him.

In December 1781, Burns moved temporarily to Irvine to learn to become a flax-dresser, but during the New Year celebrations of 1781/1782 the flax shop caught fire and was sufficiently damaged to send him home to Lochlea farm.

He continued to write poems and songs and began a Commonplace Book in 1783, while his father fought a legal dispute with his landlord. The case went to the Court of Session, and Burness was upheld in January 1784, a fortnight before he died. Robert and Gilbert made an ineffectual struggle to keep on the farm, but after its failure they moved to the farm at Mossgiel, near Mauchline in March, which they maintained with an uphill fight for the next four years. During the summer of 1784, he came to know a group of girls known collectively as The Belles of Mauchline, one of whom was Jean Armour, the daughter of a stonemason from Mauchline.

His casual love affairs did not endear him to the elders of the local kirk and created for him a reputation for dissoluteness amongst his neighbours. His first illegitimate child, Elizabeth Paton Burns (1785-1817), was born to his mother’s servant, Elizabeth Paton (1760-circa 1799), as he was embarking on a relationship with Jean Armour. She bore him twins in 1786, and although her father initially forbade their marriage, they were eventually married in 1788. She bore him nine children in total, but only three survived infancy.

During a rift in his relationship with Jean Armour in 1786, and as his prospects in farming declined, he began an affair with Mary Campbell (1763-1786), to whom he dedicated the poems The Highland Lassie O, Highland Mary and To Mary in Heaven. Their relationship has been the subject of much conjecture, and it has been suggested that they may have married. They planned to emigrate to Jamaica, where Burns intended to work as a bookkeeper on a slave plantation. He was dissuaded by a letter from Thomas Blacklock, and before the plans could be acted upon, Campbell died suddenly of a fever in Greenock.

That summer, he published the first of his collections of verse,

Poems, Chiefly in the Scottish dialect,

which created a sensation and has been recognised as a significant literary event.

which created a sensation and has been recognised as a significant literary event.

At the suggestion of his brother, Robert Burns published his poems in the volume Poems, Chiefly in the Scottish dialect, known as the Kilmarnock volume. First proposals were published in April 1786 before the poems were finally published in Kilmarnock in July 1786 and sold for 3 shillings. Brought out by John Wilson, a local printer in Kilmarnock, it contained much of his best writing, including The Twa Dogs, Address to the Deil, Hallowe'en, The Cotter's Saturday Night, To a Mouse, and To a Mountain Daisy, many of which had been written at Mossgiel farm. The success of the work was immediate, and soon he was known across the country.

Burns was invited to Edinburgh on 14 December 1786 to oversee the preparation of a revised edition, the first Edinburgh edition, by William Creech, which was finally published on 17 April 1787 (within a week of this event, Burns sold his copyright to Creech for 100 guineas). In Edinburgh, he was received as an equal by the city's brilliant men of letters and was a guest at aristocratic gatherings, where he bore himself with unaffected dignity. Here he encountered, and made a lasting impression on, the 16-year-old Walter Scott, who described him later with great admiration:

| “ | His person was strong and robust; his manners rustic, not clownish, a sort of dignified plainness and simplicity which received part of its effect perhaps from knowledge of his extraordinary talents. His features are presented in Mr Nasmyth's picture but to me it conveys the idea that they are diminished, as if seen in perspective. I think his countenance was more massive than it looks in any of the portraits ... there was a strong expression of shrewdness in all his lineaments; the eye alone, I think, indicated the poetical character and temperament. It was large, and of a dark cast, and literally glowed when he spoke with feeling or interest. I never saw such another eye in a human head, though I have seen the most distinguished men of my time. | „ |

|

— Walter Scott |

||

His stay in the city resulted in some lifelong friendships, among which were those with Lord Glencairn, and Frances Anna Dunlop (1730-1815), who became his occasional sponsor and with whom he corresponded for the rest of his life. He embarked on a relationship with the separated Agnes 'Nancy' McLehose (1758-1841), with whom he exchanged passionate letters under pseudonyms (Burns called himself 'Sylvander' and Nancy 'Clarinda'). When it became clear that Nancy would not be easily seduced into a physical relationship, Burns moved on to Jenny Clow (1766-1792), Nancy's domestic servant, who bore him a son, Robert Burns Clow in 1788. His relationship with Nancy concluded in 1791 with a final meeting in Edinburgh before she sailed to Jamaica for what transpired to be a short-lived reconciliation with her estranged husband. Before she left, he sent her the manuscript of Ae Fond Kiss as a farewell to her.

In Edinburgh in early 1787 he met James Johnson, a struggling music engraver and music seller with a love of old Scots songs and a determination to preserve them. Burns shared this interest and became an enthusiastic contributor to The Scots Musical Museum. The first volume of this was published in 1787 and included three songs by Burns. He contributed 40 songs to volume 2, and would end up responsible for about a third of the 600 songs in the whole collection as well as making a considerable editorial contribution. The final volume was published in 1803.

On his return to Ayrshire on 18 February 1788, he resumed his relationship with Jean Armour and took a lease on the farm of Ellisland near Dumfries on 18 March (settling there on 11 June) but trained as an exciseman should farming continue to prove unsuccessful. He was appointed duties in Customs and Excise in 1789 and eventually gave up the farm in 1791. Meanwhile, he was writing at his best, and in November 1790 had produced Tam O' Shanter. About this time he was offered and declined an appointment in London on the staff of the Star newspaper, and refused to become a candidate for a newly-created Chair of Agriculture in the University of Edinburgh, although influential friends offered to support his claims. After giving up his farm he removed to Dumfries.

It was at this time that, being requested to write lyrics for The Melodies of Scotland, he responded by contributing over 100 songs. He made major contributions to George Thomson's A Select Collection of Original Scottish Airs for the Voice as well as to James Johnson's The Scots Musical Museum. Arguably his claim to immortality chiefly rests on these volumes which placed him in the front rank of lyric poets. Burns described how he had to master singing the tune before he composed the words:

| “ | My way is: I consider the poetic sentiment, correspondent to my idea of the musical expression, then chuse my theme, begin one stanza, when that is composed - which is generally the most difficult part of the business - I walk out, sit down now and then, look out for objects in nature around me that are in unison or harmony with the cogitations of my fancy and workings of my bosom, humming every now and then the air with the verses I have framed. when I feel my Muse beginning to jade, I retire to the solitary fireside of my study, and there commit my effusions to paper, swinging, at intervals, on the hind-legs of my elbow chair, by way of calling forth my own critical strictures, as my, pen goes. | „ |

|

—Robert Burns |

||

Burns also worked to collect and preserve Scottish folk songs, sometimes revising, expanding, and adapting them. One of the better known of these collections is The Merry Muses of Caledonia (the title is not Burns's), a collection of bawdy lyrics that were popular in the music halls of Scotland as late as the 20th century. Many of Burns's most famous poems are songs with the music based upon older traditional songs. For example, Auld Lang Syne is set to the traditional tune Can Ye Labour Lea, A Red, Red Rose is set to the tune of Major Graham and The Battle of Sherramuir is set to the Cameronian Rant.

His direct literary influences in the use of Scots in poetry were Allan Ramsay (1686-1758) and Robert Fergusson. Burns's poetry also drew upon a substantial familiarity and knowledge of Classical, Biblical, and English literature, as well as the Scottish Makar tradition. Burns was skilled in writing not only in the Scots language but also in the Scottish English dialect of the English language. Some of his works, such as Love and Liberty (also known as The Jolly Beggars), are written in both Scots and English for various effects.

His themes included republicanism (he lived during the French Revolutionary period) and Radicalism which he expressed covertly in Scots Wha Hae, Scottish patriotism, anticlericalism, class inequalities, gender roles, commentary on the Scottish Kirk of his time, Scottish cultural identity, poverty, sexuality, and the beneficial aspects of popular socialising (carousing, Scotch whisky, folk songs, and so forth). Burns and his works were a source of inspiration to the pioneers of liberalism, socialism and the campaign for Scottish self-government, and he is still widely respected by political activists today, ironically even by conservatives and establishment figures because after his death Burns became drawn into the very fabric of Scotland's national identity. It is this, perhaps unique, ability to appeal to all strands of political opinion in the country that have led him to be widely acclaimed as the national poet.

Burns's views on these themes in many ways parallel those of William Blake, but it is believed that, although contemporaries, they were unaware of each other. Burns's works are less overtly mystical.

He is generally classified as a proto-Romantic poet, and he influenced William Wordsworth, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and Percy Bysshe Shelley greatly. The Edinburgh literati worked to sentimentalise Burns during his life and after his death, dismissing his education by calling him a "heaven-taught ploughman." Burns would influence later Scottish writers, especially Hugh MacDiarmid,

who fought to dismantle the sentimental cult that had dominated Scottish literature in MacDiarmid's opinion.

who fought to dismantle the sentimental cult that had dominated Scottish literature in MacDiarmid's opinion.

Robert Burns was initiated into Lodge St David Tarbolton on 4 July 1781, when he was 22. He was passed and raised on 1 October 1781. Later his lodge became dormant and Burns joined Lodge St James Tarbolton Kilwinning number 135. The location of the Temple where he was made a Freemason is unknown, but on 30 June 1784 the meeting place of the lodge became the “Manson Inn” in Tarbolton, and one month later, on 27 July 1784, Burns became Depute Master, which he held until 1788, often honoured with supreme command.

Although regularly meeting in Tarbolton, the “Burns Lodge” also removed itself to hold meetings in Mauchline. During 1784 he was heavily involved in Lodge business, attending all nine meetings, passing and raising brethren and generally running the Lodge. Similarly, in 1785 he was equally involved as Depute Master, where he again attended all nine lodge meetings amongst other duties of the Lodge. During 1785 he initiated and passed his brother Gilbert being raised on 1 March 1788. He must have been a very popular and well-respected Depute Master, as the minutes show that there were more lodge meetings well attended during the Burns period than at any other time.

At a meeting of Lodge St. Andrew in Edinburgh in 1787, in the presence of the Grand Master and Grand Lodge of Scotland, Burns was toasted by the Grand Master, Francis Chateris. When he was received into Edinburgh Lodges, his occupation was recorded as a “poet”. In early 1787, he was feted by the Edinburgh Masonic fraternity. The Edinburgh period of Burns's life was fateful, as further editions of the Kilmarnock Edition were sponsored by the Edinburgh Freemasons, ensuring that his name spread around Scotland and subsequently to England and abroad.

During his tour of the South of Scotland, as he was collecting material for The Scots Musical Museum, he visited lodges throughout Ayrshire and became an honorary member of a number of them. On 18 May 1787 he arrived at Eyemouth, Berwickshire, where a meeting was convened of Royal Arch and Burns became a Royal Arch Mason. On his journey home to Ayrshire, he passed through Dumfries (where he later lived), the site of the Globe Inn, which he described as his "favourite howff"(or "inn"). Burns's accommodations at the inn, which is still in use, can be visited by arrangement. His final resting place, the Burns Mausoleum, is also in Dumfries at St.Michaels Kirk. He was posthumously given the freedom of the town.

On 25 July 1787, after being re-elected Depute Master, he presided at a meeting where several well-known Masons were given honorary membership. During his Highland tour, he visited many other lodges. During the period from his election as Depute Master in 1784, Lodge St James had been convened 70 times. Burns was present 33 times and was 25 times the presiding officer. His last meeting at his mother lodge, St James Kilwinning, was on 11 November 1788.

He joined Lodge Dumfries St Andrew Number 179 on 27 December 1788. Out of the six Lodges in Dumfries, he joined the one which was the weakest. The records of this lodge are scant, and we hear no more of him until 30 November 1792, when Burns was elected Senior Warden. From this date until his final meeting in the Lodge on 14 April 1796, it appears that the Lodge met only five times. There are no records of Burns visiting any other Lodges.

On 28th August 1787 Burns visited Stirling and passed through Bridge of Allan on his way to the Roman fort at Braco.

In 1793 he wrote his poem "By Allan Stream" [1] ??

On 28th August 1787 Burns visited Stirling and passed through Bridge of Allan on his way to the Roman fort at Braco.

In 1793 he wrote his poem "By Allan Stream" [1] ??

As his health began to give way, Burns began to age prematurely and fell into fits of despondency. The habits of intemperance (alleged mainly by temperance activist James Currie) are said to have aggravated his long-standing rheumatic heart condition. In fact, his death was caused by bacterial endocarditis exacerbated by a streptococcal infection reaching his blood following a dental extraction in winter 1795, and it was no doubt further affected by the three months of famine culminating in the Dumfries Food Riots of March 1796, and on 21 July 1796 he died in Dumfries at the age of 37. The funeral took place on 25 July 1796, the day his son Maxwell was born. A memorial edition of his poems was published to raise money for his wife and children, and within a short time of his death, money started pouring in from all over Scotland to support them.

There are many organizations around the world named after Burns, as well as a large number of statues and memorials. Organisations include the Robert Burns Fellowship of the University of Otago, and the Burns Club Atlanta in the United States. Towns named after Robert Burns include Burns, New York, and Burns, Oregon. Burns' birthplace in Alloway is now a public museum, and significant 19th-century monuments to him stand in Alloway and Edinburgh. In the suburb of Summerhill in Dumfries, the majority of the streets have names with Burns connotations. A BR Standard Class 7 steam locomotive was named after him, along with a later British Rail Class 87 electric locomotive, No.87035.

The Royal Mail has twice issued postage stamps commemorating Burns. In 1966, two stamps were issued, priced fourpence and 1 shilling and threepence, both carrying Burns's portrait. In 1996, an issue commemorating the bicentenary of his death comprised four stamps, priced 19 pence, 25 pence, 41 pence and 60 pence, and included quotes from Burns's poems.

Robert Burns is pictured on the £5 banknote (since 1971) of the Clydesdale Bank, one of the Scottish banks with the right to issue banknotes. On the reverse of the note there is a vignette of a field mouse and a wild rose which refers to Burns's poem "Ode to a mouse". In September 2007, the Bank of Scotland redesigned their banknotes and Robert Burns' statue is now portrayed on the reverse side of new £5.

In 2009 the Royal Mint will issue a commemorative two pound coin featuring a quote from Auld Lang Syne.

In 1996, a musical called Red Red Rose won third place at a competition for new musicals in Denmark. The musical was about Burns's life and he was played by John Barrowman. On 25 January 2008 a musical play about the love affair between Robert Burns and Nancy McLehose entitled "Clarinda", written by Mike Gibb and Kevin Walsh, premiered in Edinburgh before touring Scotland. In April 2008 a cast CD of the score was released

(www.clarindathemusical.com)

Burns Night, effectively a second national day, is celebrated on 25 January with Burns suppers around the world, and is still more widely observed than the official national day, Saint Andrew's Day, or the proposed North American celebration Tartan Day. The format of Burns suppers has not changed since Robert's death in 1796. The basic format starts with a general welcome and announcements followed with the Selkirk Grace. After the grace comes the piping and cutting of the haggis, where Robert's famous Address To a Haggis is read and the haggis is cut open. The event usually allows for people to start eating just after the haggis is presented. This is when the reading called the "immortal memory", an overview of Robert's life and work, is given; the event usually concludes with the singing of Auld Lang Syne.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

[en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_Burns,

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Music_of_Scotland].

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

[en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_Burns,

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Music_of_Scotland].All text is available under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License. Date: February 2009. |

Photo Credits:

(1) Robert Burns,

(3) Scottish Flag,

(4) Highland Gathering Peine,

(7) James Scott Skinner,

(8) Peerie Willie Johnson,

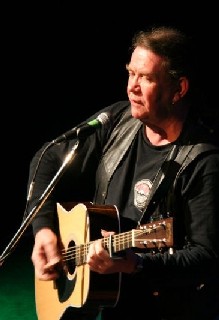

(10) Dick Gaughan,

(11) Niel Gow (unknown);

(2) Alloway Kirk,

(6) Tam O Shanter

(by www.robertburns.org);

(5) Dan McCafferty,

(16) Donnie Munro

(by Martin Kielty, Big Noise);

(9) Melrose Abbey,

(15) The McCalmans (by Walkin' Tom);

(12) Ewan MacColl & Peggy Seeger

(by Ben Harker, Class Act);

(13) Haggis,

(14) Tannahill Weavers

(by Adolf 'gorhand' Goriup);

(17) Iain Mackintosh & Hamish Imlach (by The Mollis);

(18) GNU Logo (by GNU Project);

(19) Wikipedia Logo (by Wikipedia).

|

To the German FolkWorld |

© The Mollis - Editors of FolkWorld; Published 03/2009

All material published in FolkWorld is © The Author via FolkWorld. Storage for private use is allowed and welcome. Reviews and extracts of up to 200 words may be freely quoted and reproduced, if source and author are acknowledged. For any other reproduction please ask the Editors for permission. Although any external links from FolkWorld are chosen with greatest care, FolkWorld and its editors do not take any responsibility for the content of the linked external websites.