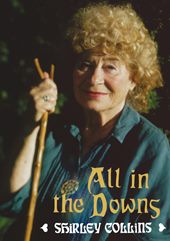

"Shirley Collins is without doubt one of England's greatest cultural treasures," says Billy Bragg about the folk singer who was a significant contributor to the English folk revival of the 1960s and 1970s. Bragg had recently published a book about the skiffle music phenomenon[66] and doesn't fail to mention that blues shouter Redd Sullivan and trad singer Shirley Collins were disputing which version of American folk songs that had emigrated from the British Isles was the most approbriate to perform: Sullivan would want to sing it the way he heard it on a Library of Congress recording, while Collins would prefer the version she had discovered in Cecil Sharp House.

Traditional Irish group Altan are delighted to present their first printed collection of instrumental music. Spanning thirty years, twelve studio albums and comprising 222 tunes, this book delves into the history, folklore and the composers and musical heroes from whom the music was collected.

Each chapter begins with an insight into the thought process behind the making of each album. Harmonic arrangements have been specially edited for accompanists.

Traditional Irish group Altan are delighted to present their first printed collection of instrumental music. Spanning thirty years, twelve studio albums and comprising 222 tunes, this book delves into the history, folklore and the composers and musical heroes from whom the music was collected.

Each chapter begins with an insight into the thought process behind the making of each album. Harmonic arrangements have been specially edited for accompanists.

Martin Tourish (ed.), Altan: The Tunes.

2018, pp206

Altan's version of the traditional Irish song "An Mhaighdean Mhara" (The Mermaid, see lyrics below)

from their 1993 album "Island Angel" inspired Erin Hart's

third mystery thriller, False Mermaid. Hart once again combines forensics and archaeology with Irish mythology:

American pathologist Nora Gavin remains haunted by the unsolved murder of her sister Tríona years ago.

She had fled to Ireland where she had met archaeologist Cormac Maguire and became involved in a couple of mysteries

(see "Haunted Ground" [47]

and "Lake of Sorrows" [50]).

But now Nora is driven back home revisiting old clues, e.g. what is the significance of the False Mermaid seeds (Floerkea proserpinacoides) found on Tríona’s body?

At the same time Cormac visits his sick father in Donegal and hears the tale of a fisherman's wife who disappeared a century ago.

Had she been murdered by her husband? Or had she been a selkie, a creature part human and part seal, who returned to the sea? Cormac's

father's acquaintance Roz has been investigating:

Altan's version of the traditional Irish song "An Mhaighdean Mhara" (The Mermaid, see lyrics below)

from their 1993 album "Island Angel" inspired Erin Hart's

third mystery thriller, False Mermaid. Hart once again combines forensics and archaeology with Irish mythology:

American pathologist Nora Gavin remains haunted by the unsolved murder of her sister Tríona years ago.

She had fled to Ireland where she had met archaeologist Cormac Maguire and became involved in a couple of mysteries

(see "Haunted Ground" [47]

and "Lake of Sorrows" [50]).

But now Nora is driven back home revisiting old clues, e.g. what is the significance of the False Mermaid seeds (Floerkea proserpinacoides) found on Tríona’s body?

At the same time Cormac visits his sick father in Donegal and hears the tale of a fisherman's wife who disappeared a century ago.

Had she been murdered by her husband? Or had she been a selkie, a creature part human and part seal, who returned to the sea? Cormac's

father's acquaintance Roz has been investigating:

»Shape-shifting and fairy-bride archetypes have always been my bread and butter as a folklorist.

There's a famous Donegal song, An Mhaighdean Mhara, about a sea maid tricked into

marriage with a human, who eventually leaves her family and returns to the sea. ...

There were loads of stories about mermaids and selkies collected in this part of the world,

but there's one detail that makes An Mhaighdean Mhara stand out. The sea maid has a

Christian name and a surname-- ...

In local parish census records from 1901, I stumbled across a fisherman called P.J. Heaney ...

He did have a common-law wife, who disappeared under rather mysterious circumstances in 1896 ...

I've come to believe that she was murdered--most likely by her husband ...«

This is the setting for two complex parallel stories leading up to a showdown on top of the cliffs of Donegal.

Though emotionally on the edge, Nora and Cormac still find some time to visit a local pub and listen to fine traditional Irish music ...

Erin Hart, False Mermaid. Scribner, 2011, ISBN 978- 1-41656-377-8

![]() Altan @ FROG

Altan @ FROG

www.altan.ie

Irish flutist Brian Dunning (formerly of Nightnoise ft. Johnny Cunningham, Tríona Ní Dhomhnaill, Mícheál Ó Domhnaill)

has collaborated with keyboardist Jeff Johnson since the late 1980s recording several Contemporary Celtic albums together

(plus a track in Martin Scorcese's Gangs of New York).

Their new album Eirlandia offers meditative and cinematic instrumental music that was inspired by and

serves as a soundtrack for Stephen R. Lawhead's latest fantasy novel In The Region Of The Summer Stars,

set in the fictive Celtic land of Eirlandia. Their music brings to life Lawhead's creation

and portrays the feelings and experiences of some of its characters.

Johnson and Dunning previously had made music to accompany other Lawhead books, including the Song of Albion and King Raven series.

Irish flutist Brian Dunning (formerly of Nightnoise ft. Johnny Cunningham, Tríona Ní Dhomhnaill, Mícheál Ó Domhnaill)

has collaborated with keyboardist Jeff Johnson since the late 1980s recording several Contemporary Celtic albums together

(plus a track in Martin Scorcese's Gangs of New York).

Their new album Eirlandia offers meditative and cinematic instrumental music that was inspired by and

serves as a soundtrack for Stephen R. Lawhead's latest fantasy novel In The Region Of The Summer Stars,

set in the fictive Celtic land of Eirlandia. Their music brings to life Lawhead's creation

and portrays the feelings and experiences of some of its characters.

Johnson and Dunning previously had made music to accompany other Lawhead books, including the Song of Albion and King Raven series.

![]() Stephen R. Lawhead, In the Region of the Summer Stars: Eirlandia, Book One.

Tor Books, 2018, ISBN 978-0-7653-8344-0, pp336, €22,98 (www.stephenlawhead.com)

Stephen R. Lawhead, In the Region of the Summer Stars: Eirlandia, Book One.

Tor Books, 2018, ISBN 978-0-7653-8344-0, pp336, €22,98 (www.stephenlawhead.com)

Jeff Johnson & Brian Dunning, Eirlandia. ARK Music, 2018

Mary James wrote her first song as a six-year-old, called Mean Mary From Alabam. The name stuck ever since.

These days Mean Mary James is best known for her fast banjo picking, however, she is also no mean guitarist, fiddler and singer.

She writes acoustic pop songs drawing on folk, blues and bluegrass music, and she is also an

author of several novels co-written with her mother Jean. Thus Mean Mary's latest album with her brother Frank, Blazing, is a collection of

banjo and guitar instrumentals and the soundtrack to the mystery thriller, Hell Is Naked.

Mary James wrote her first song as a six-year-old, called Mean Mary From Alabam. The name stuck ever since.

These days Mean Mary James is best known for her fast banjo picking, however, she is also no mean guitarist, fiddler and singer.

She writes acoustic pop songs drawing on folk, blues and bluegrass music, and she is also an

author of several novels co-written with her mother Jean. Thus Mean Mary's latest album with her brother Frank, Blazing, is a collection of

banjo and guitar instrumentals and the soundtrack to the mystery thriller, Hell Is Naked.

Jean & Mary James, Hell Is Naked.

2018, (www.jamesauthors.com)

Mean Mary, Blazing. Woodrock Records, 2018

![]() Mean Mary @ FROG

Mean Mary @ FROG

www.meanmary.com

Shirley Collins herself remembers the time like this:

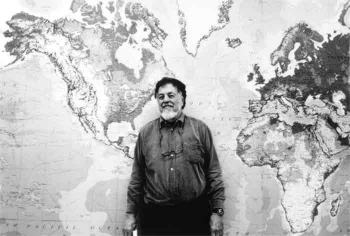

In an earlier book, Shirley Collins recalled her memories of a field recording trip with Alan Lomax in the deep South of America in 1959. However, she hadn't detailled her musical career before, especially the personal drama that made her abandon singing in the late 1970s at all.

But let's get back in time. Shirley Collins was born in 1935 and grew up with her older sister Dolly in the Hastings area of East Sussex. So, not a very exciting place, but she cannot remember ever being bored as a child: Dolly and I had music!

Shirley moved in with American folk collector Alan Lomax, who had come to Britain to avoid the McCarthy witch-hunt. She joined Lomax in The Ramblers (featuring Ewan MacColl and Peggy Seeger) and on a field recording trip in the American South (noted for the discovery of Mississippi Fred McDowell).

Collins married Ashley Hutchings in 1971. He eventually left Steeleye Span and assembled the first incarnation of the Albion Country Band. It became a musically fruitful partnership. However, Hutchings ran off with an actress. The painful divorce caused dysphonia (which she only mentions briefly), leading to her retirement from music altogether. She subsequently worked for The British Museum, Cecil Sharp House, Oxfam, South-East Arts and The Job Centre until she reached retirement age in 1995.

In 2002, Fellside Records produced a box set of Shirley's recordings from 1955 to 1978 and asked her for a contribution to an English/Australian folk song sampler.

In 2014, Earth Recordings released a set featuring covers of songs she had recorded. It served as a fundraiser for a documentary film about her life. She eventually released Lodestar, her first new album in 38 years, and sang in public again.

Interspersed with lots of song fragments, All in the Downs is a vivid and matter-of-fact reflection on Shirley's life, her music - and the landscape, the South Downs of her beloved Sussex.

Is cosúil gur mheath tú nó gur thréig tú an greann You seem to be pining and forsaking the fun Tá an sneachta go freasach fá bhéal na mbeann' The snowdrifts are heavy by the fords in the burn Do chúl buí daite is do bhéilín sámh Your bright golden tresses and smile gentle and mild Siúd chugaibh Mary Chinidh 's í 'ndiaidh an Éirne 'shnámh I give you Mary Kinney who has swum the ocean wide A mháithrín mhilis duirt Máire Bhán "Darling mother," cries Máire Bhán Fá bhruach an chladaigh 's fá bhéal na trá From the banks of the ocean and down by the tide Maighdean mhara mo mhaithrín ard "Mermaid, my mother, my pride" Siúd chugaibh Mary Chinidh 's í 'ndiaidh an Éirne 'shnámh I give you Mary Kinney who has swum the ocean wide Tá mise tuirseach agus beidh go lá I'm tired and weary and will be 'til dawn Mo Mháire bhroinngheal 's mo Phádraig bán For my darling Mary and my Pádraid bán Ar bharr na dtonna 's fá bhéal na trá As I ride on the billows and drift with the tide Siúd chugaibh Mary Chinidh 's í 'ndiaidh an Éirne 'shnámh I give you Mary Kinney who has swum the ocean wide

|

Photo Credits:

(1ff) Book/CD Covers,

(6) Shirley Collins,

(7) Seamus Ennis,

(8) Alan Lomax,

(9) Ewan MacColl,

(10) Altan,

(11) Mean Mary,

(from website/author/publishers).