FolkWorld #63 07/2017

Music of Scotland

Scotland (Alba)

Scotland (Alba)

Capital: Edinburgh

Population: 5,4 mio.

Location:

Scotland is a country that is part of the United Kingdom and covers the northern third of the island of Great Britain.

It shares a border with England to the south, and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean, with the North Sea to the east and the North Channel and Irish Sea to the south-west. In addition to the mainland, the country is made up of more than 790 islands, including the Northern Isles and the Hebrides.

With the Festival Interceltique Lorient and the Rudolstadt Festival, Scotland is in the focus of this year's summer festivals.

6-9 July 2017

6-9 July 2017

There's no doubt that Scottish music was very

popular in Germany starting with the folk revivals in the 1970s. But then

there were also some years with little that was the wee bit more than just

good. In the last decade things have changed, though: The Scottish folk

scene bursts with creativity and innvation, a vibrant scene has developed,

and Trad Scots has become a hot tip for young people, too. Meaning that the

music simply forced us to finally do a focus on Scotland. Apart from the

fact that in 2017 we can also show our European solidarity...

A Man For A’ That – A World

Music Tribute To Robert Burns

Amy MacDonald

Breabach

Ceilidh Minogue

Fred Morrison

Kist O' Riches

Mairearad and Anna

Mairi Campbell

Niteworks

Sketch

Yorkston Thorne Khan

The 47th edition of the Lorient Interceltic Festival in Brittany, France

will celebrate the colours, music and warm energy of Scotland !

Scottish pipe bands have never missed an edition since the beginning in 1971. A lot of talented musicians from

the "Far North" of the Celtic world have been discovered during the almost half a century of festival that followed.

The 2017 festival will celebrate a country which succeeds in mixing tradition and modernity, two

key aspects of intercelticism. It will be the third edition in the history of the festival dedicated to this

Celtic nation, located in northernmost tip of the British Isles and native land of Macbeth and William Wallace.

Amy MacDonald

Andrew Frater

Andy Gibbs

Andy Wilson

Blazin' Fiddles

Breabach

Bruce MacGregor

Calum Stewart

Capercaillie

Corrina Hewat

Elephant Sessions

Fara

Fred Morrison

Garry Innes

Ian Duncan

Isle of Cumbrae Pipe Band

Methil and District Pipe Band

Mischa McPherson Trio

Ross Ainslie & Ali Hutton

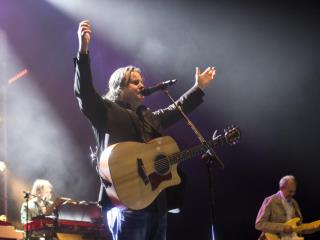

RunRig

Scotland's Wild Heart

Talisk

Tannara

Tribute to Gordon Duncan

Scotland is internationally known for its traditional music, which remained vibrant throughout the 20th century and into the 21st, when many traditional forms worldwide lost popularity to pop music. In spite of emigration and a well-developed connection to music imported from the rest of Europe and the United States, the music of Scotland has kept many of its traditional aspects; indeed, it has itself influenced many forms of music.

Many outsiders associate Scottish folk music almost entirely with the Great Highland Bagpipe, which has long played an important part in Scottish music. Although this particular form of bagpipe developed exclusively in Scotland, it is not the only Scottish bagpipe, and other bagpiping traditions remain across Europe. The earliest mention of bagpipes in Scotland dates to the 15th century although they are believed to have been introduced to Scotland as early as the 6th century by the Gaels of Ireland. The pìob mhór, or Great Highland Bagpipe, was originally associated with both hereditary piping families and professional pipers to various clan chiefs; later, pipes were adopted for use in other venues, including military marching. Piping clans included the Clan Henderson, MacArthurs, MacDonalds, McKays and, especially, the MacCrimmon, who were hereditary pipers to the Clan MacLeod.

Early music

Stringed instruments have been known in Scotland from at least the Iron Age; the first evidence of lyres outwith the Greco-Roman world were found on the Isle of Skye, dating from 2300 BC, making it Europe's oldest surviving stringed instrument. Bards, who acted as musicians, but also as poets, story tellers, historians, genealogists and lawyers, relying on an oral tradition that stretched back generations, were found in Scotland as well as Wales and Ireland. Often accompanying themselves on the harp, they can also be seen in records of the Scottish courts throughout the medieval period. Scottish church music from the later Middle Ages was increasingly influenced by continental developments, with figures like 13th-century musical theorist Simon Tailler studying in Paris, before returned to Scotland where he introduced several reforms of church music. Scottish collections of music like the 13th-century 'Wolfenbüttel 677', which is associated with St Andrews, contain mostly French compositions, but with some distinctive local styles. The captivity of James I in England from 1406 to 1423, where he earned a reputation as a poet and composer, may have led him to take English and continental styles and musicians back to the Scottish court on his release. In the late 15th century a series of Scottish musicians trained in the Netherlands before returning home, including John Broune, Thomas Inglis and John Fety, the last of whom became master of the song school in Aberdeen and then Edinburgh, introducing the new five-fingered organ playing technique. In 1501 James IV refounded the Chapel Royal within Stirling Castle, with a new and enlarged choir and it became the focus of Scottish liturgical music. Burgundian and English influences were probably reinforced when Henry VII's daughter Margaret Tudor married James IV in 1503. James V (1512–42) was a major patron of music. A talented lute player, he introduced French chansons and consorts of viols to his court and was patron to composers such as David Peebles (c. 1510–1579?).

The Scottish Reformation, directly influenced by Calvinism, was generally opposed to church music, leading to the removal of organs and a growing emphasis on metrical psalms, including a setting by David Peebles commissioned by James Stewart, 1st Earl of Moray. The most important work in Scottish reformed music was probably A forme of Prayers published in Edinburgh in 1564. The return from France of James V's daughter, Mary, Queen of Scots in 1561, renewed the Scottish court as a centre of musical patronage and performance. The Queen played the lute, virginals and (unlike her father) was a fine singer. She was brought many influences from the French court where she had been educated, employing lutenists and viol players in her household. Mary's position as a Catholic gave a new lease of life to the choir of the Scottish Chapel Royal in her reign, but the destruction of Scottish church organs meant that instrumentation to accompany the mass had to employ bands of musicians with trumpets, drums, fifes, bagpipes and tabors. The outstanding Scottish composer of the era was Robert Carver (c.1485–c.1570) whose works included the nineteen-part motet 'O Bone Jesu'. James VI, king of Scotland from 1567, was a major patron of the arts in general. He rebuilt the Chapel Royal at Stirling in 1594 and the choir was used for state occasions like the baptism of his son Henry. He followed the tradition of employing lutenists for his private entertainment, as did other members of his family.

When he came south to take the throne of England in 1603 as James I, he removed one of the major sources of patronage in Scotland. The Scottish Chapel Royal was now used only for occasional state visits, as when Charles I returned in 1633 to be crowned, bringing many musicians from the English Chapel Royal for the service, and it began to fall into disrepair. From now on the court in Westminster would be the only major source of royal musical patronage.

Folk music

Scottish folk music (also Scottish traditional music) is music that uses forms that are identified as part of the Scottish musical tradition. There is evidence that there was a flourishing culture of popular music in Scotland during the late Middle Ages, but the only song with a melody to survive from this period is the "Pleugh Song". After the Reformation, the secular popular tradition of music continued, despite attempts by the Kirk, particularly in the Lowlands, to suppress dancing and events like penny weddings. The first clear reference to the use of the Highland bagpipes mentions their use at the Battle of Pinkie Cleugh in 1547. The Highlands in the early seventeenth century saw the development of piping families including the MacCrimmons, MacArthurs, MacGregors and the Mackays of Gairloch. There is also evidence of adoption of the fiddle in the Highlands. Well-known musicians included the fiddler Pattie Birnie and the piper Habbie Simpson. This tradition continued into the nineteenth century, with major figures such as the fiddlers Neil and his son Nathaniel Gow. There is evidence of ballads from this period. Some may date back to the late Medieval era and deal with events and people that can be traced back as far as the thirteenth century. They remained an oral tradition until they were collected as folk songs in the eighteenth century.

Capercaillie @ FolkWorld:

FW#3

Capercaillie @ FolkWorld:

FW#3,

#8,

#12,

#16,

#17,

#23,

#24,

#28,

#29,

#31

#34,

#36

#38,

#52

www.capercaillie.co.uk The earliest printed collection of secular music comes from the seventeenth century. Collection began to gain momentum in the early eighteenth century and, as the kirk's opposition to music waned, there were a flood of publications including Allan Ramsay's verse compendium The Tea Table Miscellany (1723) and The Scots Musical Museum (1787 to 1803) by James Johnson and Robert Burns. From the late nineteenth century there was renewed interest in traditional music, which was more academic and political in intent. In Scotland collectors included the Reverend James Duncan and Gavin Greig. Major performers included James Scott Skinner. This revival began to have a major impact on classical music, with the development of what was in effect a national school of orchestral and operatic music in Scotland, with composers such as included Alexander Mackenzie, William Wallace, Learmont Drysdale, Hamish MacCunn and John McEwen.

After World War II traditional music in Scotland was marginalised, but remained a living tradition. This was changed by individuals including Alan Lomax, Hamish Henderson and Peter Kennedy, through collecting, publications, recordings and radio programmes. Acts that were popularised included John Strachan, Jimmy MacBeath, Jeannie Robertson and Flora MacNeil. In the 1960s there was a flourishing folk club culture and Ewan MacColl emerged as a leading figure in the revival in Britain. They hosted traditional performers, including Donald Higgins and the Stewarts of Blairgowrie, beside English performers and new Scottish revivalists such as Robin Hall, Jimmie Macgregor, The Corries and the Ian Campbell Folk Group. There was also a strand of popular Scottish music that benefited from the arrival of radio and television, which relied on images of Scottishness derived from tartanry and stereotypes employed in music hall and variety, exemplified by the TV programme The White Heather Club which ran from 1958 to 1967, hosted by Andy Stewart and starring Moira Anderson and Kenneth McKeller. The fusing of various styles of American music with British folk created a distinctive form of fingerstyle guitar playing known as folk baroque, pioneered by figures including Davy Graham and Bert Jansch. Others totally abandoned the traditional element including Donovan and the Incredible String Band, who have been seen as developing psychedelic folk. Acoustic groups who continued to interpret traditional material through into the 1970s included Ossian, Silly Wizard, The Boys of the Lough, Battlefield Band, The Clutha and the Whistlebinkies.

Celtic rock developed as a variant of the electric folk by Scottish groups including the JSD Band and Spencer's Feat. Five Hand Reel, who combed Irish and Scottish personnel, emerged as the most successful exponents of the style. From the late 1970s the attendance at, and numbers of, folk clubs began to decrease, as new musical and social trends began to dominate. However, in Scotland the circuit of ceilidhs and festivals helped prop up traditional music. Two of the most successful groups of the 1980s that emerged from this dance band circuit were Runrig and Capercaillie. A by-product of the Celtic Diaspora was the existence of large communities across the world that looked for their cultural roots and identity to their origins in the Celtic nations. From the USA this includes Scottish bands Seven Nations, Prydein and Flatfoot 56. From Canada are bands such as Enter the Haggis, Great Big Sea, The Real Mckenzies and Spirit of the West.

Development

There is evidence that there was a flourishing culture of popular music in Scotland in the Late Middle Ages. This includes the long list of songs given in The Complaynt of Scotland (1549). Many of the poems of this period were also originally songs, but for none has a notation of their music survived. Melodies have survived separately in the post-Reformation publication of The Gude and Godlie Ballatis (1567), which were spiritual satires on popular songs, adapted and published by the brothers James, John and Robert Wedderburn. The only song with a melody to survive from this period is the "Pleugh Song". After the Reformation, the secular popular tradition of music continued, despite attempts by the Kirk, particularly in the Lowlands, to suppress dancing and events like penny weddings at which tunes were played.

The first clear reference to the use of the Highland bagpipes is from a French history, which mentions their use at the Battle of Pinkie Cleugh in 1547. George Buchanan claimed that they had replaced the trumpet on the battlefield. This period saw the creation of the ceòl mór (the great music) of the bagpipe, which reflected its martial origins, with battle-tunes, marches, gatherings, salutes and laments. The Highlands in the early seventeenth century saw the development of piping families including the MacCrimmonds, MacArthurs, MacGregors and the Mackays of Gairloch. There is also evidence of adoption of the fiddle in the Highlands with Martin Martin noting in his A Description of the Western Isles of Scotland (1703) that he knew of eighteen players in Lewis alone. Well-known musicians included the fiddler Pattie Birnie (c. 1635–1721) and the piper Habbie Simpson (1550–1620). This tradition continued into the nineteenth century, with major figures such as the fiddlers Neil (1727–1807) and his son Nathaniel Gow (1763–1831), who, along with a large number of anonymous musicians, composed hundreds of fiddle tunes and variations.

There is evidence of ballads from this period. Some may date back to the late Medieval era and deal with events and people that can be traced back as far as the thirteenth century, including "Sir Patrick Spens" and "Thomas the Rhymer", but for which there is no evidence until the eighteenth century. Scottish ballads are distinct, showing some pre-Christian influences in the inclusion of supernatural elements such as the fairies in the Scottish ballad "Tam Lin". They remained an oral tradition until the increased interest in folk songs in the eighteenth century led collectors such as Bishop Thomas Percy to publish volumes of popular ballads.

Early song collection

In Scotland the earliest printed collection of secular music was by publisher John Forbes, produced in Aberdeen in 1662 as Songs and Fancies: to Thre, Foure, or Five Partes, both Apt for Voices and Viols. It was printed three times in the next twenty years, and contained seventy-seven songs, of which twenty-five were of Scottish origin. In the eighteenth century publications included John Playford's Collection of original Scotch-tunes, (full of the highland humours) for the violin (1700), Margaret Sinkler's Music Book (1710), James Watson's Choice Collection of Comic and Serious Scots Poems both Ancient and Modern 1711. The oppression of secular music and dancing by the kirk began to ease between about 1715 and 1725 and the level of musical activity was reflected in a flood musical publications in broadsheets and compendiums of music such as the makar Allan Ramsay's verse compendium The Tea Table Miscellany (1723), William Thomson's Orpheus Caledonius: or, A collection of Scots songs (1733), James Oswald's The Caledonian Pocket Companion (1751), and David Herd's Ancient and modern Scottish songs, heroic ballads, etc.: collected from memory, tradition and ancient authors (1776). These were drawn on for the most influential collection, The Scots Musical Museum published in six volumes from 1787 to 1803 by James Johnson and Robert Burns, which also included new words by Burns. The Select Scottish Airs collected by George Thomson and published between 1799 and 1818 included contributions from Burns and Walter Scott. Among Scott's early works was the influential collection of ballads The Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border (1802–03).

Revivals

First revival

From the late nineteenth century there was renewed interest in traditional music, which was more academic and political in intent. Harvard professor Francis James Child's (1825–96) eight-volume collection The English and Scottish Popular Ballads (1882–92) has been the most influential on defining the repertoire of subsequent performers and the English music teacher Cecil Sharp was probably the most important in understanding of the nature of folk song. In Scotland collectors included the Reverend James Duncan (1848–1917) and Gavin Greig (1856–1914), who collected over 1,000 songs, mainly from Aberdeenshire. The tradition continued with figures including James Scott Skinner (1843–1927), known as the "Strathspey King", who played the fiddle in venues ranging from the local functions in his native Banchory, to urban centres of the south and at Balmoral. In 1923 the Royal Scottish Country Dance Society was founded in an attempt to preserve traditional Scottish dance that were threatened by the introduction of the continental ballroom dances such as the waltz or quadrilles. The accordion also began to be a central instrument at Highland balls and dances.

This revival began to have a major impact on classical music, with the development of what was in effect a national school of orchestral and operatic music in Scotland. Major composers included Alexander Mackenzie (1847–1935), William Wallace (1860–1940), Learmont Drysdale (1866–1909), Hamish MacCunn (1868–1916) and John McEwen (1868–1948). Mackenzie, who studied in Germany and Italy and mixed Scottish themes with German Romanticism, is best known for his three Scottish Rhapsodies (1879–80, 1911), Pibroch for violin and orchestra (1889) and the Scottish Concerto for piano (1897), all involving Scottish themes and folk melodies. Wallace's work included an overture, In Praise of Scottish Poesie (1894). Drysdale's work often dealt with Scottish themes, including the overture Tam O’ Shanter (1890), the cantata The Kelpie (1891). MacCunn's overture The Land of the Mountain and the Flood (1887), his Six Scotch Dances (1896), his operas Jeanie Deans (1894) and Dairmid (1897) and choral works on Scottish subjects have been described by I. G. C. Hutchison as the musical equivalent of the Scots Baronial castles of Abbotsford and Balmoral. Similarly, McEwen's Pibroch (1889), Border Ballads (1908) and Solway Symphony (1911) incorporated traditional Scottish folk melodies.

Second revival

After visiting Celtic Connections 2017, Nordic Notes Records' Christian Pliefke was blown away by the diversity of Scottish music.

It was clear to him that he had to present some of the amazing young artists he had become fond of.

The great new compilation Folk and Great Tunes from Scotland features 2 songs from:

Breabach,

Twelfth Day,

Shooglenifty,

Paul McKenna Band,

Iona Fyfe Band,

Rachel Newton,

Skerryvore,

Sarah-Jane Summers and Juhani Silvola,

Fara,

Gary Innes,

Tannara,

Manran,

Treacherous Orchestra,

Rura,

Claire Hastings,

The Elephant Sessions.

Christian Pliefke is inclined to return, so maybe there's more in the pipeline...

Various Artists "Folk and Great Tunes from Scotland",

Nordic Notes/Tasal, 2017

After World War II traditional music in Scotland was marginalised, but, unlike in England, it remained a much stronger force, with the Céilidh house still present in rural communities until the early 1950s and traditional material still performed by the older generation, even if the younger generation tended to prefer modern styles of music. This decline was changed by the actions of individuals such as American musicologist Alan Lomax, who collected numerous songs in Scotland that were issued by Columbia Records around 1955. Radio broadcasts by Lomax, Hamish Henderson and Peter Kennedy (1922–2006) were also important in raising awareness of the tradition, particularly Kennedy's As I Roved Out, which was largely based around Scottish and Irish music. The School of Scottish Studies was founded at University of Edinburgh in 1951, with Henderson as a research fellow and a collection of songs begun by Calum Maclean (1915–60). Acts that were popularised included John Strachan (1875–1958), Jimmy MacBeath (1894–1972), Jeannie Robertson (1908–75) and Flora MacNeil (born 1928). A number festivals also popularised the music, such as Edinburgh People's Festival (1951–53) and Aberdeen Folk Festival (1963–). In the 1960s there was a flourishing folk club culture. The first folk club was founded in London by Ewan MacColl (1915–89), who emerged as a leading figure in the revival in Britain, recording influential records such as Scottish Popular Ballads (1956). Scottish folk clubs were less dogmatic than their English counterparts, which rapidly moved to an all English folk song policy, and continued to encourage a mixture of Scottish, Irish, English and American material. Early on they hosted traditional performers, including Donald Higgins and the Stewarts of Blairgowrie, beside English performers and new Scottish revivalists such as Robin Hall (1936–98), Jimmie Macgregor (born 1930) and The Corries. A number of these new performers, including the Ian Campbell Folk Group, emerged from the skiffle movement.

There was also a strand of popular Scottish music that benefited from the arrival of radio and television, which relied on images of Scottishness derived from tartanry and stereotypes employed in music hall and variety. Proponents included Andy Stewart (1933–93), whose weekly programme The White Heather Club ran in Scotland from 1958 to 1967. Frequent guests included Moira Anderson (born 1938) and Kenneth McKeller (1927–2010), who enjoyed their own programmes. The programmes and their music were immensely popular, although their version of Scottish music and identity was despised by many modernists.

The fusing of various styles of American music with British folk created a distinctive form of fingerstyle guitar playing known as folk baroque, pioneered by figures including Davy Graham and Bert Jansch. This led in part to British progressive folk music, which attempted to elevate folk music through greater musicianship, or compositional and arrangement skills. Many progressive folk performers continued to retain a traditional element in their music, including Jansch who became a member of the band Pentangle in 1967. Others largely abandoned the traditional element of their music. Particularly important were Donovan (who was most influenced by emerging progressive folk musicians in America such as Bob Dylan) and the Incredible String Band, who from 1967 incorporated a range of influences including medieval and Eastern music into their compositions, leading to the development of psychedelic folk, which had a considerable impact on progressive and psychedelic rock. Acoustic groups who continued to interpret traditional material through into the 1970s included Ossian and Silly Wizard. The Boys of the Lough and Battlefield Band, emerged from the flourishing Glasgow folk scene. Also from this scene were the highly influential The Clutha, whose line up, with two fiddlers, was later augmented by the piper Jimmy Anderson, and the Whistlebinkies, who pursued a strongly instrumental format, relying on traditional instruments, including a Clàrsach (Celtic harp).

Celtic rock

Various Artists "Classic English and Scottish Ballads",

Smithsonian Folkways, 2017

Celtic rock developed as a variant of the electric folk, playing traditional English folk music with rock instrumentation, developed by Fairport Convention and its members from 1969. Donovan used the term "Celtic rock" to describe the folk rock he created for his Open Road album in 1970, featured a song with "Celtic rock" as its title. The adoption of electric folk heavily influenced by Scottish traditional music produced groups including the JSD Band and Spencer's Feat. Out of the wreckage of the latter in 1974, guitarist Dick Gaughan (born 1948) formed probably the most successful band in this genre Five Hand Reel, who combed Irish and Scottish personnel, before he embarked on an influential solo career.

From the late 1970s the attendance at, and numbers of, folk clubs began to decrease, as new musical and social trends, including punk rock, new wave and electronic music began to dominate. However, in Scotland the circuit of ceilidhs and festivals helped prop up traditional music. Two of the most successful groups of the 1980s emerged from this dance band circuit. From 1978, when they began to release original albums, Runrig produced highly polished Scottish electric folk, including the first commercially successful album with the all Gaelic Play Gaelic in 1978. From the 1980s Capercaillie combined Scottish folk music, electric instruments and haunting vocals to considerable success. While bagpipes had become an essential element in Scottish folk bands they were much rarer in electric folk outfits, but were successfully integrated into their sound by Wolfstone from 1989, who focused on a combination of highland music and rock.

One by-product of the Celtic Diaspora was the existence of large communities across the world that looked for their cultural roots and identity to their origins in the Celtic nations. While it seems young musicians from these communities usually chose between their folk culture and mainstream forms of music such as rock or pop, after the advent of Celtic punk relatively large numbers of bands began to emerge styling themselves as Celtic rock. This is particularly noticeable in the USA and Canada, where there are large communities descended from Irish and Scottish immigrants. From the USA this includes Scottish bands Seven Nations, Prydein and Flatfoot 56. From Canada are bands such as Enter the Haggis, Great Big Sea, The Real Mckenzies and Spirit of the West. These groups were naturally influenced by American forms of music, some containing members with no Celtic ancestry and commonly singing in English.

Pop, rock and fusion

Pop and rock were slow to get started in Scotland and produced few bands of note in the 1950s or 1960s, though thanks to accolades by David Bowie and others, the Edinburgh-based band 1-2-3 (later Clouds), active 1966–71, have belatedly been acknowledged as a definitive precursor of the progressive rock movement. However, by the 1970s bands such as the Average White Band, Nazareth, and the Sensational Alex Harvey Band began to have international success. The biggest Scottish pop act of the 1970s however (at least in terms of sales) were undoubtedly the Bay City Rollers. Several of the members of the internationally successful rock band AC/DC were born in Scotland, including original lead singer Bon Scott and guitarists Malcolm and Angus Young, though by the time they began playing, all three had moved to Australia. George Young, Angus and Malcolm's older brother, found success as a member of the Australian band The Easybeats, later produced some of AC/DC's records and formed a songwriting partnership with Dutch expat Harry Vanda. Similarly Mark Knopfler was partly raised in Scotland.

During the '60s Scotland contributed 2 innovative rock musicians who were central to the international scene; folk/psychedelia guitarist/singer/songwriter Donovan (Donovan Phillips Leitch), and blues-rock/jazz-rock bassist/composer Jack Bruce (John Symon Asher Bruce). Traces of Scottish literary and musical influences can be found in both Donovan's and Bruce's work.

Thou bonnie wood o Craigielea

Near thee I pass'd life's early day

An won ma dearie's hert in thee

A weaver by trade and song-writer and poet by calling, Robert Tannahill of Paisley (1774-1810)

[41]

left a great legacy of over 100 songs, of a quality that compare with SCotland's national bard Robert Burns.

The fourth volume in Fred Freeman’s recording series with songs such as

"Thou Bonnie Wood O Craigielea"

and "The Wandering Bard"

reflects the breadth of influence that informed Tannahill's compositions, including elements of Irish, Jewish and Baroque music.

This is married with Freeman’s contemporary approach in the Scottish folk idiom with

missing tunes newly composed, choruses created and texts altered.

The Complete Songs of Robert Tannahill Volume 4 features

Claire Hastings,

Rod Paterson,

Fiona Hunter,

Brian O hEadhra,

Ross Kennedy,

Wendy Weatherby and the late Nick Keir,

plus instrumentalists such as Sandy Brechin, Stewart Hardy, Aaron Jones, Angus Lyon ...

Various Artists "The Complete Songs of Robert Tannahill Volume 4 - Thou Bonnie Wood & Craigielea",

Brechin All Records, 2017

Donovan's music on 1965's Fairytale anticipated the British-folk rock revival. Donovan pioneered psychedelic-rock with Sunshine Superman in 1966. Donovan's decidedly Celtic rock directions can be found on his later albums like Open Road and H.M.S. Donovan, Donovan's session crew during the 60s included Jimmy Page, John Bonham and John Paul Jones who would later go on to form Led Zeppelin. Donovan is said to be an early influence and encouragement for Marc Bolan founder of T. Rex.

Jack Bruce co-founded Cream along with Eric Clapton and Ginger Baker in 1966, debuting with the album Fresh Cream. Fresh Cream and the launch of Cream are considered a pivotal moment in blues-rock history, introducing virtuosity and improvisation to the form. Bruce, as a member of Tony Williams Lifetime (along with John McLaughlin and Larry Young) on Emergency!, similarly contributed to a seminal jazz-rock work that predated Bitches Brew by Miles Davis.

Scotland produced a few punk bands of note, such as The Exploited, The Rezillos, The Skids, The Fire Engines, and the Scars. However, it was not until the post-punk era of the early 1980s, that Scotland really came into its own, with bands like Cocteau Twins, Orange Juice, The Associates, Simple Minds, Maggie Reilly, Annie Lennox (Eurythmics), Hue and Cry, Goodbye Mr. Mackenzie, The Jesus and Mary Chain, Wet Wet Wet, Big Country, The Proclaimers and Josef K. Since the 1980s Scotland has produced several popular rock and alternative rock acts.

Most recently, Scottish piping has included a renaissance for cauldwind pipes such as smallpipes and border pipes, which use cold, dry air as opposed to the moist air of mouth-blown pipes. Other pipers such as Gordon Duncan and Fred Morrison began to explore new musical genres on many kinds of pipes. The accordion also gained in popularity during the 1970s due to the renown of Phil Cunningham, whose distinctive piano accordion style was an integral part of the band Silly Wizard. Numerous musicians continued to follow more traditional styles including Alex Beaton.

A more recent trend has been to fuse traditional Celtic with world music, rock and jazz (see Celtic fusion). This has been championed by musicians such as Shooglenifty, innovators of the house fusion acid croft, Peatbog Faeries, The Easy Club, jazz fusion bands, puirt à beul mouth musicians Talitha MacKenzie and Martin Swan, pioneering singers Savourna Stevenson and Christine Primrose. Other modern musicians include the late techno-piper Martyn Bennett (who used hip hop beats and sampling), Hamish Moore, Roger Ball, Hamish Stuart, Jim Diamond and Sheena Easton.

Scotland produced many indie bands in the 1980s, including Primal Scream, The Soup Dragons, The Jesus and Mary Chain, The Blue Nile, Teenage Fanclub, 18 Wheeler, The Pastels and BMX Bandits being some of the best examples. The following decade also saw a burgeoning scene in Glasgow, with the likes of The Almighty, Arab Strap, Belle & Sebastian, Camera Obscura, The Delgados, Bis and Mogwai.

The late 1990s and 2000s saw Scottish guitar bands continue to achieve critical or commercial success, examples include Franz Ferdinand, Frightened Rabbit, Biffy Clyro, Texas, Travis, KT Tunstall, Amy Macdonald, Paolo Nutini, The View, Idlewild, Shirley Manson of Garbage, Glasvegas, We Were Promised Jetpacks, The Fratellis, and Twin Atlantic. Scottish extreme metal bands include Man Must Die and Cerebral Bore. One of the most famous and successful electronic music producers, Calvin Harris, is also Scottish.

Jazz

Scotland has a strong jazz tradition and has produced many world class musicians since the 1950s, notably Jimmy Deuchar, Bobby Wellins and Joe Temperley. A long-standing problem was the lack of opportunities within Scotland to play with international musicians. Since the 1970s this has been addressed by Edinburgh clubowner Bill Kyle (the JazzBar) and enthusiast-run organisations such as Platform and then Assembly Direct, which have provided improved performance opportunities.

Perhaps the best known contemporary Scottish jazz musician is Tommy Smith. Again, the Edinburgh Jazz and Blues Festival brings some of the best jazz musicians in the world to Scotland every year, although, increasingly, other cities (such as Glasgow and Dundee) also run international jazz festivals.

Instruments

Accordion

“If you’ve been through Argyll at all in your life everywhere you look you’ll hear the album and its origins in

every hill and fern and sunset in this beautiful but often lonely and isolated part of the world.”

(Peter Greenwood)

Various Artists "In the Wild Country", MusicMakesMe/The Walking Theatre Co., 2016

Though often derided as Scottish kitsch, the accordion has long been a part of Scottish music. Country dance bands, such as that led by the renowned Jimmy Shand, have helped to dispel this image. In the early 20th century, the melodeon (a variety of diatonic button accordion) was popular among rural folk, and was part of the bothy band tradition. More recently, performers like Phil Cunningham (of Silly Wizard) and Sandy Brechin have helped popularise the accordion in Scottish music.

Bagpipes

Though bagpipes are closely associated with Scotland by many outsiders, the instrument (or, more precisely, family of instruments) is found throughout large swathes of Europe, North Africa and South Asia. The most common bagpipe heard in modern Scottish music is the Great Highland Bagpipe, which was spread by the Highland regiments of the British Army. Historically, numerous other bagpipes existed, and many of them have been recreated in the last half-century. Also during the 19th century bagpipes were played on ships sailing off to war to keep the men's hopes up and to bring good luck in the coming war.

The classical music of the Great Highland Bagpipe is called Pìobaireachd, which consists of a first movement called the urlar (in English, the 'ground' movement,) which establishes a theme. The theme is then developed in a series of movements, growing increasingly complex each time. After the urlar there is usually a number of variations and doublings of the variations. Then comes the taorluath movement and variation and the crunluath movement, continuing with the underlying theme. This is usually followed by a variation of the crunluath, usually the crunluath a mach (other variations: crunluath breabach and crunluath fosgailte) ; the piece closes with a return to the urlar.

Bagpipe competitions are common in Scotland, for both solo pipers and pipe bands. Competitive solo piping is currently popular among many aspiring pipers, some of whom travel from as far as Australia to attend Scottish competitions. Other pipers have chosen to explore more creative usages of the instrument. Different types of bagpipes have also seen a resurgence since the 70s, as the historical border pipes and Scottish smallpipes have been resuscitated and now attract a thriving alternative piping community.

The pipe band is another common format for highland piping, with top competitive bands including the Victoria Police Pipe Band from Australia (formerly), Northern Ireland's Field Marshal Montgomery, the Republic of Ireland's Laurence O'Toole pipe band, Canada's 78th Fraser Highlanders Pipe Band and Simon Fraser University Pipe Band, and Scottish bands like Shotts and Dykehead Pipe Band and Strathclyde Police Pipe Band. These bands, as well as many others, compete in numerous pipe band competitions, often the World Pipe Band Championships, and sometimes perform in public concerts.

Fiddle

Scottish traditional fiddling encompasses a number of regional styles, including the bagpipe-inflected west Highlands, the upbeat and lively style of Norse-influenced Shetland Islands and the Strathspey and slow airs of the North-East. The instrument arrived late in the 17th century, and is first mentioned in 1680 in a document from Newbattle Abbey in Midlothian, Lessones For Ye Violin.

In the 18th century, Scottish fiddling is said to have reached new heights. Fiddlers like William Marshall and Niel Gow were legends across Scotland, and the first collections of fiddle tunes were published in mid-century. The most famous and useful of these collections was a series published by Nathaniel Gow, one of Niel's sons, and a fine fiddler and composer in his own right. Classical composers such as Charles McLean, James Oswald and William McGibbon used Scottish fiddling traditions in their Baroque compositions.

Scottish fiddling is the root of much American folk music, such as Appalachian fiddling, but is most directly represented in Cape Breton, Nova Scotia, an island on the east coast of Canada, which received some 25,000 emigrants from the Scottish Highlands during the Highland Clearances of 1780–1850. Cape Breton musicians such as Natalie MacMaster, Ashley MacIsaac, and Jerry Holland have brought their music to a worldwide audience, building on the traditions of master fiddlers such as Buddy MacMaster and Winston Scotty Fitzgerald.

Among native Scots, Aly Bain and Alasdair Fraser are two of the most accomplished, following in the footsteps of influential 20th-century players such as James Scott Skinner, Hector MacAndrew, Angus Grant and Tom Anderson. The growing number of young professional Scottish fiddlers makes a complete list impossible.

The Annual Scots Fiddle Festival which runs each November showcases the great fiddling tradition and talent in Scotland.

Guitar

The history of the guitar in traditional music is recent, as is that of the cittern and bouzouki, which in the forms used in Scottish and Irish music only date to the late 1960s. The guitar featured prominently in the folk revival of the early 1960s with the likes of Archie Fisher, the Corries, Hamish Imlach, Robin Hall and Jimmie MacGregor. The virtuoso playing of Bert Jansch was widely influential, and the range of instruments was widened by the Incredible String Band. Notable artists include Tony McManus, Dave MacIsaac, Peerie Willie Johnson and Dick Gaughan. Other notable guitarists in Scottish music scene include Kris Drever of Fine Friday and Lau, and Ross Martin of Cliar, Daimh and Harem Scarem.

Harp

Material evidence suggests that lyres and/or harp, or clarsach, has a long and ancient history in Scotland, with Iron Age lyres dating from 2300BC. The harp was regarded as the national instrument until it was replaced with the Highland bagpipes in the 15th century. Stone carvings in the East of Scotland support the theory that the harp was present in Pictish Scotland well before the 9th century and may have been the original ancestor of the modern European harp and even formed the basis for Scottish pibroch, the folk bagpipe tradition.

Barring illustrations of harps in the 9th century Utrecht psalter, only thirteen depictions exist in Europe of any triangular chordophone harp pre-11th century, and all thirteen of them come from Scotland. Pictish harps were strung from horsehair. The instruments apparently spread south to the Anglo-Saxons, who commonly used gut strings, and then west to the Gaels of the Highlands and to Ireland. The earliest Irish word for a harp is in fact Cruit, a word which strongly suggests a Pictish provenance for the instrument. The surname MacWhirter, Mac a' Chruiteir, means son of the harpist, and is common throughout Scotland, but particularly in Carrick and Galloway.

The Clàrsach (Gd.) or Cláirseach (Ga.) is the name given to the wire-strung harp of either Scotland or Ireland. The word begins to appear by the end of the 14th century. Until the end of the Middle Ages it was the most popular musical instrument in Scotland, and harpers were among the most prestigious cultural figures in the courts of Irish/Scottish chieftains and Scottish kings and earls. In both countries, harpers enjoyed special rights and played a crucial part in ceremonial occasions such as coronations and poetic bardic recitals. The Kings of Scotland employed harpers until the end of the Middle Ages, and they feature prominently in royal iconography. Several Clarsach players were noted at the Battle of the Standard (1138), and when Alexander III (died 1286) visited London in 1278, his court minstrels with him, records show payments were made to one Elyas, "King of Scotland's harper." One of the nicknames for the Scottish harp is "taigh nan teud", the house of strings.

Three medieval Gaelic harps survived into the modern period, two from Scotland (the Queen Mary Harp and the Lamont Harp) and one in Ireland (the Brian Boru harp), although artistic evidence suggests that all three were probably made in the western Highlands.

The playing of this Gaelic harp with wire strings died out in Scotland in the 18th century and in Ireland in the early 19th century. As part of the late 19th century Gaelic revival, the instruments used differed greatly from the old wire-strung harps. The new instruments had gut strings, and their construction and playing style was based on the larger orchestral pedal harp. Nonetheless the name "clàrsach" was and is still used in Scotland today to describe these new instruments. The modern gut-strung clàrsach has thousands of players, both in Scotland and Ireland, as well as North America and elsewhere. The 1931 formation of the Clarsach Society kickstarted the modern harp renaissance. Recent harp players include Savourna Stevenson, Maggie MacInnes, and the band Sileas. Notable events include the Edinburgh International Harp Festival, which recently staged the world record for the largest number of harpists to play at the same time.

Tin whistle

One of the oldest tin whistles still in existence is the Tusculum whistle, found with pottery dating to the 14th and 15th centuries; it is currently in the collection of the Museum of Scotland. Today the whistle is a very common instrument in recorded Scottish music. Although few well-known performers choose the tin whistle as their principal instrument, it is quite common for pipers, flute players, and other musicians to play the whistle as well.

Bodhran

The bodhran as currently used is a (re)import from Ireland, and is highly popular in Scottish folk music. However, it has been suggested that the instrument previously existed in Scotland before its reintroduction.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

[en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Music_of_Scotland,

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scottish_folk_music].

Wikipedia® is a registered trademark of the Wikimedia Foundation, Inc., a non-profit organization.

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License.

Date: June 2017.

Photo Credits:

(1) Scotland,

(2) Daimh 'The Hebridean Sessions',

(3) Rudolstadt Festival,

(4) Capercaillie,

(5) Festival Interceltique Lorient,

(6) Runrig,

(7) Various Artists 'Folk and Great Tunes from Scotland',

(8) Talisk,

(9) Various Artists 'Classic English and Scottish Ballads',

(11) Various Artists 'The Complete Songs of Robert Tannahill Volume 4 - Thou Bonnie Wood & Craigielea',

(13) Gordon Duncan,

(14) Various Artists 'In the Wild Country',

(15) Joy Dunlop,

(16) Fara,

(17) Blazin' Fiddles,

(18) Tannara,

(19) Corrina Hewat

(unknown/website);

(7) Breabach

(by Adolf „gorhand“ Goriup);

(10) Manran,

(12) Fred Morrison

(by Walkin' Tom).

FolkWorld - Home of European Music

Layout & Idea of FolkWorld © The Mollis - Editors of FolkWorld

Layout & Idea of FolkWorld © The Mollis - Editors of FolkWorld